Okay, let’s talk about something that sounds super boring but is actually pretty important if you’ve got a traditional IRA sitting around—Required Minimum Distributions, or RMDs for short. Trust me, I know the name alone makes your eyes glaze over, but stick with me here.

So what exactly is an RMD for IRA accounts? Basically, it’s the minimum amount Uncle Sam says you’ve got to pull out of your retirement accounts each year once you hit a certain age. We’re talking traditional IRAs, SEP IRAs, SIMPLE IRAs, and most employer retirement plans like 401(k)s. Think of it as the government finally saying, “Okay, you’ve had your fun avoiding taxes all these years—time to pay up!”

When you contributed to your traditional IRA over the years, you got those sweet tax deductions, right? Your money’s been growing tax-free or tax-deferred for decades. However, the IRS isn’t exactly known for their generosity, so they want to make sure they eventually collect taxes on all that deferred income and growth you’ve been racking up. That’s literally the whole point of RMDs—making sure the government gets its cut before you, you know, shuffle off this mortal coil.

Now, things have gotten a bit messy lately. The RMD rules have been through more changes than a chameleon at a paint store, thanks to the SECURE Act of 2019 and then SECURE Act 2.0. Congress keeps tweaking the ages, the penalties, and various other details, which honestly makes planning a bit of a headache.

But I should mention some good news right up front: Roth IRAs are exempt from RMDs during your lifetime. Yep, if you’ve got a Roth IRA, you can let that baby grow tax-free for as long as you want without being forced to take withdrawals. That’s one of the major perks of Roth accounts, and honestly, it’s a pretty sweet deal.

- Determining Your RMD Starting Point and Deadlines

- Calculating the RMD Amount

- Real-World Case Study: Calculating Your First RMD

- Penalties, Corrections, and Tax Forms

- Advanced RMD Strategies and Tax Planning

- Special Rules for Inherited IRAs

- Case Study: Eleanor and David – The Adult Child Inheriting After RBD

- Case Study: Lily's Journey from Minor to Adult Beneficiary

- Case Study: Sarah's Spousal Options and the SECURE 2.0 Game Changer

- Option 2: Traditional Inherited IRA

- Case Study: The Successor Beneficiary Trap

- Case Study: The Trust Beneficiary Tax Trap

- Special Considerations for Inherited Roth IRAs

- Simplifying RMD Compliance

Determining Your RMD Starting Point and Deadlines

How the RMD age changed

Alright, so when do these mandatory withdrawals actually kick in? That’s the million-dollar question, and honestly, the answer keeps changing because Congress can’t seem to make up its mind.

Let me show you how the RMD age has evolved over time—and buckle up, because it’s been quite the journey:

The RMD Age Through the Years:

Before 2020: You had to start taking RMDs at age 70½. Yeah, that weird half-age thing was as annoying as it sounds.

2020-2022: The SECURE Act bumped it up to age 72 if you turned 70½ after December 31, 2019.

2023-2032: SECURE Act 2.0 raised the bar again to age 73 starting January 1, 2023. So if you’re hitting 73 now, that’s your starting line.

2033 and beyond: Get ready for another change—the RMD age is scheduled to jump to age 75 in 2033.

I know, I know—it’s like they’re moving the goalposts every few years. Nevertheless, the general trend is in your favor if you’re not retired yet. More time for that money to grow tax-deferred!

Birth year reference table

This table makes it all clear:

| Year of Birth | Applicable RMD Age | First Distribution Year | Required Beginning Date (Deadline) |

| Before July 1, 1949 | 70½ | Year attaining 70½ | April 1 of the following year |

| July 1, 1949 – Dec 31, 1950 | 72 | Year attaining 72 | April 1 of the following year |

| Jan 1, 1951 – Dec 31, 1958 | 73 | Year attaining 73 | April 1 of the following year |

| 1959 | 73* | 2032 | April 1, 2033 |

| 1960 and later | 75 | Year attaining 75 | April 1 of the following year |

Notice

There’s a technical drafting issue in SECURE 2.0 regarding people born in 1959, but the IRS and financial institutions are treating their RMD age as 73, not 75.

The April 1st Deadline Rule

Timing gets a little tricky at this point. You don’t actually have to take your very first RMD in the year you turn 73. The IRS gives you a bit of breathing room—you can wait until April 1st of the following year. Sounds generous, right?

Well, hold on. Before you get too excited, let me warn you about what I call the double-tax year trap. If you decide to delay that first RMD until April 1st of the year after you turn 73, you’re going to end up taking TWO distributions in that year. Why? Because you’ll need to take the delayed RMD from the previous year AND your regular RMD for the current year (which is due by December 31st).

Taking two RMDs in one year could bump you into a higher tax bracket, and nobody wants that surprise at tax time. Consequently, most financial advisors actually recommend taking your first RMD in the year you turn 73, not waiting until April. Just saying—sometimes it pays to not procrastinate!

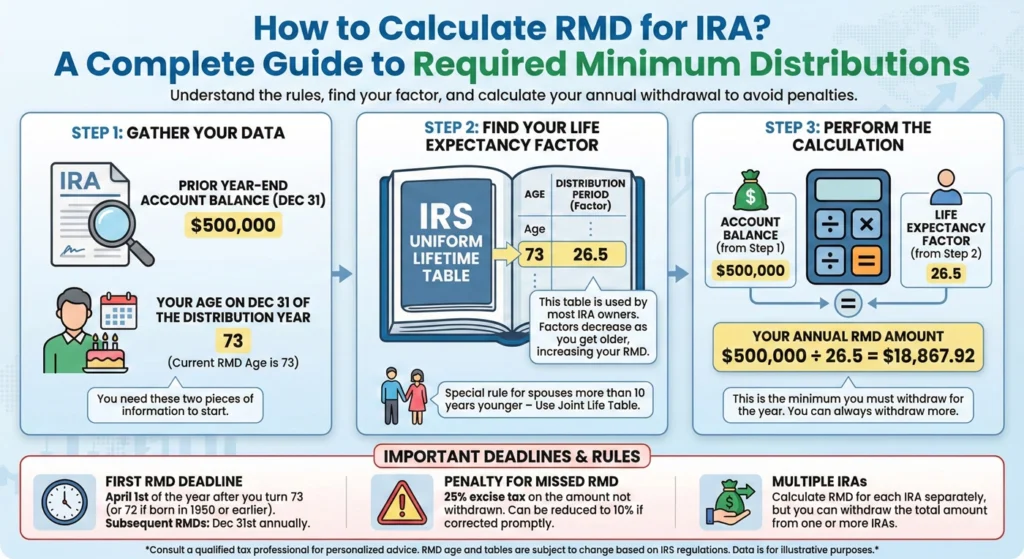

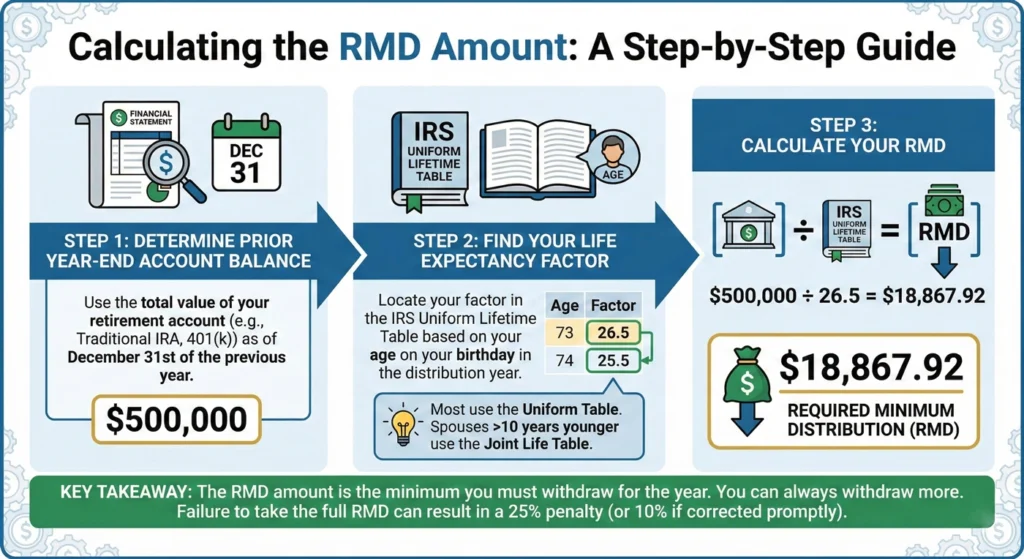

Calculating the RMD Amount

The basic formula

Okay, now we’re getting into the math part, but don’t worry—it’s not as scary as it sounds. If you’re wondering how to calculate RMD for IRA accounts, the basic formula looks like this:

RMD Amount = Account Balance (as of December 31st of the prior year) ÷ Life Expectancy Factor

That’s it! Honestly, the formula itself is pretty straightforward. The tricky part is figuring out which life expectancy factor to use (we’ll get to that in a sec).

Key factors in account valuation

When you’re looking at your account balance, you need to use the value as of December 31st of the previous year. However, it’s not always as simple as just looking at your December statement.

You might need to adjust for things like outstanding rollovers or recharacterizations that happened around year-end. Additionally, if you’ve got deferred annuities inside your IRA (honestly, not super common but it happens), there are special rules about calculating their actuarial present value. Yeah, that’s a mouthful, and in such cases, you’ll probably want to chat with a financial pro.

Which life expectancy table to use

Alright, this is where it gets a bit more interesting. The IRS has three different life expectancy tables, and which one you use can make a real difference in how much you have to withdraw. Using an RMD calculator for IRA accounts can help simplify this process, but let’s break down the tables:

Uniform Lifetime Table (Table III): This is the one most people use. If you’re unmarried, or if you’re married but your spouse isn’t the sole beneficiary of your IRA, or your spouse isn’t more than 10 years younger than you—boom, you’re using this table. It’s the standard, go-to option.

The IRS updated this table in 2022 to reflect improved mortality data, which actually works in your favor—the new factors result in slightly lower required distributions. Check out some sample factors:

Alright, this is where it gets a bit more interesting. The IRS has three different life expectancy tables, and which one you use can make a real difference in how much you have to withdraw. Using an RMD calculator for IRA accounts can help simplify this process, but let’s break down the tables:

Uniform Lifetime Table (Table III): This is the one most people use. If you’re unmarried, or if you’re married but your spouse isn’t the sole beneficiary of your IRA, or your spouse isn’t more than 10 years younger than you—boom, you’re using this table. It’s the standard, go-to option.

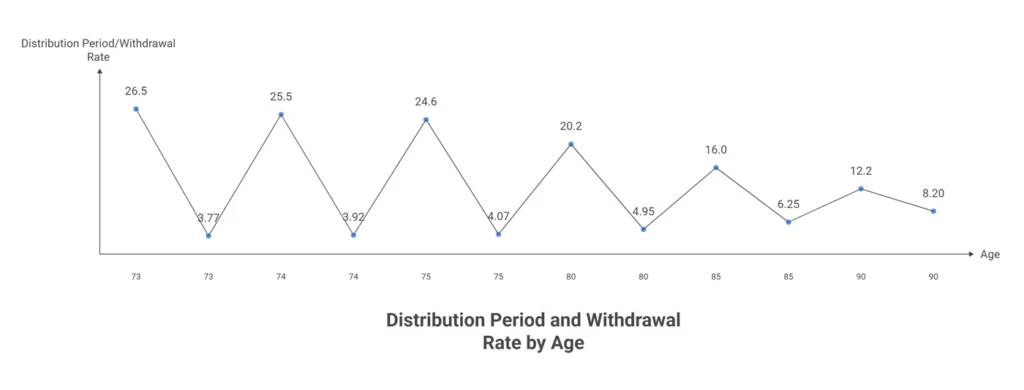

The IRS updated this table in 2022 to reflect improved mortality data, which actually works in your favor—the new factors result in slightly lower required distributions. Here are some sample factors:

| Age | Distribution Period (Factor) | Approximate Withdrawal Rate |

| 73 | 26.5 | 3.77% |

| 74 | 25.5 | 3.92% |

| 75 | 24.6 | 4.07% |

| 80 | 20.2 | 4.95% |

| 85 | 16.0 | 6.25% |

| 90 | 12.2 | 8.20% |

Joint Life Table (Table II): This one’s special. You only use this if your spouse is the sole designated beneficiary of your IRA AND they’re more than 10 years younger than you. The good news? This table usually gives you a smaller RMD because your joint life expectancy is longer. It’s like the IRS acknowledging that your money might need to last for both of you for a long time.

Single Life Expectancy Table (Table I): This is mainly for non-spouse beneficiaries who inherit an IRA. We’ll dive deeper into inherited IRA rules later, but just know this table exists for that specific situation.

The RMD Aggregation Rule

Traditional IRA aggregation

This confuses a lot of folks, so pay attention because this is actually pretty handy:

For Traditional IRAs, SEP IRAs, and SIMPLE IRAs: You have to calculate the RMD separately for each IRA account you own. However, you can add up all those RMD amounts and then withdraw the total from any combination of your IRAs. So if you’ve got three IRAs and it makes sense to pull all the money from just one of them (maybe for investment reasons), you can totally do that.

Employer plan rules

For Employer Plans (like 401(k)s, 403(b)s, etc.): Sorry, no mixing and matching here. You’ve got to calculate the RMD for each plan separately AND withdraw it from that specific plan. No aggregation allowed.

This distinction is actually pretty important for tax planning, so keep it in mind!

The Roth Distinction: 401(k) Alignment

If you have a Roth 401(k), there’s some great news: SECURE 2.0 eliminated a major disparity between Roth IRAs and Roth 401(k)s.

While Roth IRAs have never been subject to lifetime RMDs, Roth 401(k)s used to be, which forced owners to roll them over to Roth IRAs to avoid distributions. Effective for taxable years beginning after December 31, 2023 (starting in 2024), Roth 401(k) accounts are no longer subject to lifetime RMDs either. This alignment simplifies planning and lets you keep assets within an employer plan without forced liquidation.

Real-World Case Study: Calculating Your First RMD

Let me show you how this works in real life. Meet Margaret, who turns 73 in 2024. She’s never been married, so she’ll use the Uniform Lifetime Table.

Margaret’s Situation:

- Born: March 15, 1951

- Turns 73 in 2024

- Traditional IRA balance on December 31, 2023: $500,000

- No spouse, so she uses the Uniform Lifetime Table

Step 1: Determine her Life Expectancy Factor

Margaret turns 73 in 2024, so she looks up age 73 in the Uniform Lifetime Table (Table III). The factor is 26.5.

Step 2: Calculate her 2024 RMD

RMD = $500,000 ÷ 26.5 = $18,867.92

Step 3: Decide on timing

Margaret has two options:

- Take the $18,867.92 by December 31, 2024

- OR delay it until April 1, 2025

Margaret’s Decision:

Being smart about taxes, Margaret decides to take her first RMD in 2024. Why? Because if she delays until April 1, 2025, she’ll need to take TWO RMDs in 2025:

- The delayed 2024 RMD (based on the Dec 31, 2023 balance)

- Her regular 2025 RMD (based on the Dec 31, 2024 balance)

Let’s say her account grows to $510,000 by December 31, 2024. Her 2025 RMD would be:

- Factor at age 74: 25.5

- RMD = $510,000 ÷ 25.5 = $20,000

If she delays, she’d have to take approximately $38,867.92 in income in 2025 ($18,867.92 + $20,000), potentially bumping her into a higher tax bracket. By taking the first RMD in 2024, she spreads the tax burden more evenly.

Going Forward:

Each year, Margaret will:

- Look up her new age in the Uniform Lifetime Table

- Use her December 31 account balance from the prior year

- Divide the balance by the factor

- Withdraw that amount by December 31

The process repeats annually for the rest of her life.

Penalties, Corrections, and Tax Forms

The Penalty for Insufficient Distributions

Okay, real talk—you do NOT want to mess up your RMDs. The penalties used to be absolutely brutal, but the good news is this: SECURE Act 2.0 brought some relief.

If you fail to take your RMD or you take too little, you’ll face an excise tax penalty on the shortfall. But the update is encouraging: the penalty has been reduced from 50% to 25% of the amount you should have withdrawn. That’s still a hefty chunk, but it’s way better than the old 50% rate. Imagine getting hit with a penalty that’s literally half of what you were supposed to take out—ouch!

Furthermore, it gets even better—if you catch your mistake quickly and fix it during the IRS “correction window,” that penalty drops down to just 10%. So if you realize you goofed, don’t panic—just act fast and make it right.

How to Correct a Missed RMD

Let’s say you accidentally missed your RMD. First off, don’t freak out. What you need to do is:

Step one: Immediately withdraw the required amount. Like, as soon as you realize the mistake, get that money out. The faster you act, the better your case for reducing the penalty.

Step two: Report the penalty on IRS Form 5329. This is also the form where you can request a waiver of the penalty.

The thing is, the IRS actually has a heart sometimes (shocking, I know). If you can show reasonable cause for missing the RMD and you’ve already corrected the mistake, they might waive the penalty entirely. Reasonable cause could be something like a serious illness, a family emergency, or relying on incorrect advice from a professional. It’s definitely worth trying!

The Process:

- File Form 5329 for the year the distribution was missed

- Report the RMD on Line 52 and the actual withdrawal on Line 53

- Enter “RC” (Reasonable Cause) next to Line 54 and the amount of the waiver requested

- Attach a letter explaining the error

- File the form (with $0 if requesting a full waiver)

Reporting Conversions and Basis

If you’ve made non-deductible contributions to your IRA or you’ve done Roth conversions, you need to stay on top of Form 8606. This form tracks your basis (the after-tax money you’ve already put in), which is super important for figuring out what’s taxable and what’s not when you take distributions.

I know it’s another form to deal with, but trust me—accurate record-keeping now saves you major headaches (and potentially money) down the road.

Advanced RMD Strategies and Tax Planning

Qualified Charitable Distributions (QCDs)

Okay, one of my favorite RMD strategies is especially useful if you’re charitably minded: Qualified Charitable Distributions, or QCDs.

Once you hit age 70½ (yeah, that weird half-age makes a comeback here), you can make a direct transfer from your traditional IRA to a qualified charity. The maximum you can transfer is $108,000 per year, and the beautiful part? That money goes straight to the charity without ever being counted as income on your tax return.

Moreover, QCDs count toward your RMD! So you’re satisfying your distribution requirement, helping out a cause you care about, AND keeping that money out of your taxable income. It’s a triple win. Even if you don’t itemize deductions (and most people don’t anymore after the tax law changes), you still get the tax benefit. Pretty sweet deal if you ask me.

Notice

QCDs don’t work with SEP or SIMPLE IRAs—only traditional IRAs. Just a heads up.

Withdrawal Sequencing for Tax Optimization

Something to think about: the order in which you withdraw from different types of accounts can make a big difference in your lifetime tax bill.

Generally, you’ve got three buckets: taxable accounts (like regular brokerage accounts), tax-deferred accounts (traditional IRAs, 401(k)s), and tax-free accounts (Roth IRAs). There’s no one-size-fits-all strategy, but thoughtful planning can save you thousands over your retirement.

One interesting move is making in-kind transfers—that means transferring actual securities from your IRA to your regular brokerage account instead of selling them first. You satisfy your RMD and pay ordinary income tax on the current value, but then those assets are in a taxable account where future growth might be taxed at lower capital gains rates instead of ordinary income rates. It’s a bit advanced, but it’s worth discussing with a financial advisor if you’ve got significant IRA balances.

Special Rules for Inherited IRAs

Post-SECURE Act (2020 and Later) Changes

Alright, if you’re inheriting an IRA or planning your estate, buckle up because the rules changed big time in 2020.

The old “Stretch IRA” strategy—where non-spouse beneficiaries could stretch out distributions over their entire lifetime—is basically dead for most people. Thanks, Congress.

Now, most non-spouse beneficiaries who inherit an IRA after 2019 are subject to the 10-year rule. That means all the money has to come out of the inherited IRA by the end of the 10th year following the original owner’s death. You can take it out all at once, spread it over 10 years, or wait until year 10 and take it all then (though that last option usually creates a nasty tax bill).

The 10-Year Rule vs. Annual RMDs

This is where things get murky, and honestly, even the IRS seems confused about this. There’s been ongoing debate about whether you need to take annual RMDs during that 10-year period if the original owner had already started taking RMDs.

The IRS put out Notice 2024-35 basically saying, “Hey, we’re not going to penalize you for not taking annual RMDs from inherited IRAs for the past few years while we figure this out.” They’re still working on finalizing the rules, which is honestly kind of frustrating if you’re trying to do proper planning.

The Current State (as of 2025):

The Final Regulations released in July 2024 clarified that the 10-Year Rule creates two different scenarios:

Scenario 1: Owner Died Before Their RBD

- No annual RMDs required in years 1-9

- Complete account liquidation by end of year 10

- Maximum flexibility for tax planning

Scenario 2: Owner Died On or After Their RBD

- Annual RMDs required in years 1-9 based on beneficiary’s life expectancy

- Complete account liquidation by end of year 10

- Less flexibility, but the IRS waived penalties for 2021-2024

Case Study: Eleanor and David – The Adult Child Inheriting After RBD

Let me show you how this works with a real example. Eleanor died in 2024 at age 79. She was already taking her own RMDs (her Required Beginning Date was years earlier). Her son David, age 52, inherited her Traditional IRA as the Designated Beneficiary.

Because Eleanor died after her RBD, David faces both the 10-year rule AND annual RMDs. Let me show you how this plays out:

Year 1 (2025): The First Mandatory RMD

David must take an RMD starting in 2025. The calculation works like this:

First, David determines his life expectancy factor from the Single Life Table using his age in 2025 (he’ll be 53).

Factor for age 53 is 33.4

Next, Calculate the RMD

RMD = (Account Balance on Dec 31, 2024) ÷ 33.4

If the account was worth $800,000 on December 31, 2024:

RMD = $800,000 ÷ 33.4 = $23,952.10

Years 2-9: The “Subtract One” Method

For each subsequent year, David reduces his life expectancy factor by 1.0:

- Year 2 (2026): Factor = 32.4

- Year 3 (2027): Factor = 31.4

- Year 4 (2028): Factor = 30.4

- And so on through Year 9 (2033): Factor = 25.4

Each year, he divides that year’s December 31 account balance by the reduced factor.

Year 10 (2034): The Final Liquidation

By December 31, 2034, David must withdraw the entire remaining balance, regardless of what the RMD calculation would suggest.

The Key Comparison

If Eleanor had died at age 68 (before her RBD): David would have zero RMD requirements in years 1-9. He could let the account grow untouched and only need to empty it by 2034. This flexibility allows for strategic tax planning across the decade.

Since Eleanor died at age 79 (after her RBD): David must take those annual RMDs starting immediately in 2025, limiting his flexibility to manage tax brackets year by year.

Tax Planning Strategy for David:

Given that the annual RMDs (roughly 3% of the account) won’t significantly deplete the balance, David should consider taking more than the minimum each year. If he waits until 2034, he could face a massive balloon payment that pushes him into the highest tax bracket. Therefore, it’s better to spread it out strategically based on his income each year.

Eligible Designated Beneficiaries (EDBs)

Not everyone gets stuck with the 10-year rule, though. There’s a special category called Eligible Designated Beneficiaries who can still use the old life expectancy method (basically, the Stretch IRA).

EDBs include:

- Your surviving spouse (they get the most flexibility—we’ll talk about that next)

- Minor children of the deceased owner (but only until they turn 21, then the 10-year rule kicks in)

- Chronically ill or disabled individuals

- Anyone who’s not more than 10 years younger than the deceased owner (like a sibling close in age)

If you fall into one of these categories, you’ve got more options and potentially better tax treatment.

Case Study: Lily’s Journey from Minor to Adult Beneficiary

This complex scenario catches many families off guard. Robert died in 2024, leaving his IRA to his 12-year-old daughter Lily. As a minor child of the account owner, Lily qualifies as an Eligible Designated Beneficiary – but only temporarily. Her inheritance journey unfolds in three distinct phases.

Phase 1: The EDB Years (Ages 13-21)

From age 13 to 21, Lily takes annual RMDs based on her single life expectancy – the classic “Stretch IRA” approach.

Year 1 (2025): Lily turns 13. Looking at the IRS Single Life Table, the factor for age 13 is 71.8.

If the inherited IRA is worth $500,000:

2025 RMD = $500,000 ÷ 71.8 = $6,963.79

This represents only about 1.4% of the account, allowing substantial continued growth during her childhood.

Years 2-9: Each year, the factor decreases by 1.0 (Year 2 = 70.8, Year 3 = 69.8, etc.)

Phase 2: The Critical Transition at Age 21 (Year 2032)

When Lily turns 21 in 2032, everything changes. She immediately loses her EDB status and becomes a Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary.

Important Note: The IRS standardized the “age of majority” at 21 for everyone for retirement purposes, regardless of state laws. This extends the EDB period for children in states with lower ages of majority (like 18).

Phase 3: The 10-Year Clock Starts (Ages 21-31)

The 10-year liquidation period begins January 1, 2033 (the year after she reaches age 21) and ends December 31, 2042 (when she turns 31).

During this window (2033-2042), Lily must:

- Continue taking annual RMDs based on her life expectancy (since she was already taking distributions as a minor)

- Completely liquidate the account by December 31, 2042

The Compliance Danger

Custodians must rigorously track that 21st birthday. Missing the transition from the “Stretch” calculation to the “10-Year Liquidation” schedule could result in massive penalties – 25% (or 10% if corrected quickly) of the amounts that should have been withdrawn.

The Big Picture Timeline

- Ages 13-21 (9 years): Stretch IRA with minimal RMDs

- Ages 21-31 (10 years): Accelerated liquidation under the 10-year rule

- By Age 31: The inherited IRA must be completely empty

So Lily gets 19 total years of tax-deferred growth (9 years as an EDB + 10 years under the liquidation rule), not the decades-long stretch that would have been available under pre-2020 rules.th (9 years as an EDB + 10 years under the liquidation rule), not the decades-long stretch that would have been available under pre-2020 rules.

Spousal Flexibility

If you inherit an IRA from your spouse, you’ve basically hit the beneficiary jackpot in terms of flexibility.

As a surviving spouse, you can:

- Treat the inherited IRA as your own (this is usually the best move)

- Roll it over into your own IRA

- Delay RMDs until you reach age 73 (your own RMD age)

- Use the 10-year rule if you want (though why would you?)

This flexibility is huge. It essentially means that if you inherit your spouse’s IRA, it’s like it was yours all along. You won’t be forced to start taking distributions until you reach your own required beginning date, which could be years or even decades away if you’re significantly younger than your spouse was.

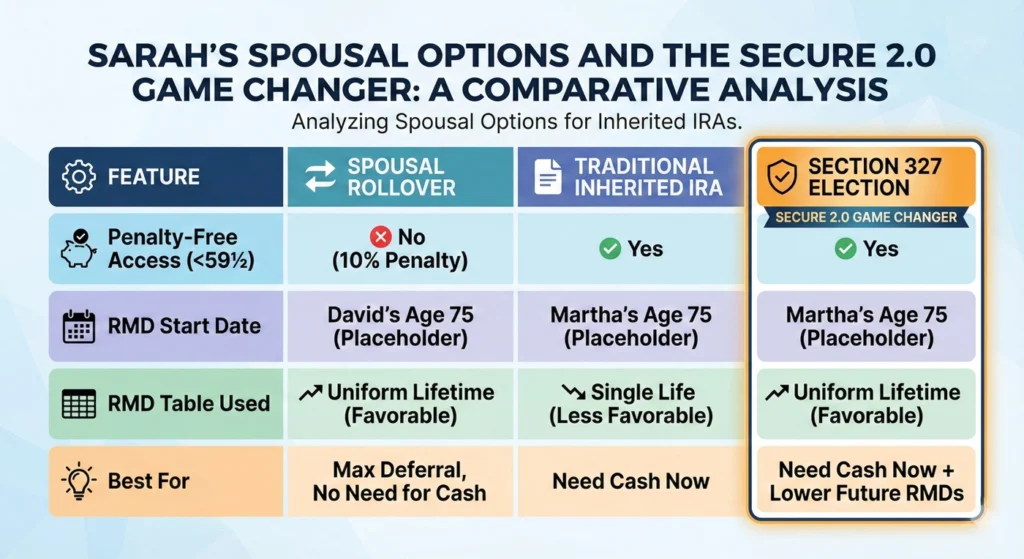

Case Study: Sarah’s Spousal Options and the SECURE 2.0 Game Changer

Let me introduce you to Sarah, age 56, who inherited her husband Michael’s $1,000,000 Traditional IRA in 2024. Michael died at age 68 – before his Required Beginning Date (which would have been age 75). Sarah is under age 59½ and needs some liquidity now but also wants to maximize long-term tax deferral. This creates a specific planning opportunity thanks to SECURE 2.0.

Option 1: Traditional Spousal Rollover

Sarah could roll the IRA into her own name, treating the assets as hers.

Pros:

- RMDs are delayed until Sarah reaches age 75 (since she was born after 1960) – maximum tax deferral

- Once RMDs begin, she uses the Uniform Lifetime Table, which results in smaller distributions than the Single Life Table

Cons:

- If Sarah needs money before age 59½, she’ll face the 10% early withdrawal penalty

- This is a significant disadvantage since she needs some liquidity now

Option 2: Traditional Inherited IRA

Sarah keeps the account as an Inherited IRA in beneficiary status.

Pros:

- All distributions are exempt from the 10% penalty (death exception) – critical for immediate liquidity needs

Cons:

- Under old rules, RMDs would have to start when Michael would have reached age 75

- She’d be forced to use the Single Life Table, which has higher divisors resulting in faster account depletion than the Uniform Table

Option 3: The SECURE 2.0 Section 327 Election (The Game Changer)

Things get really interesting at this point. Under SECURE 2.0’s Section 327, Sarah can elect to be “treated as the decedent” for RMD purposes.

How it works:

- The account remains an Inherited IRA (preserving the 10% penalty exemption)

- But RMD rules apply as if Sarah were Michael

- RMDs are delayed until Michael would have reached age 75

The Big Win: Unlike the traditional inherited IRA, Sarah gets to use the Uniform Lifetime Table (based on her age) to calculate RMDs once they begin.

The Result: This option provides the flexibility of penalty-free access if needed, combined with the favorable RMD divisors of the Uniform Table. It is mathematically superior to the Spousal Rollover for a young widow who needs access to funds before age 59½.

Check out this quick comparison:

| Feature | Spousal Rollover | Traditional Inherited IRA | Section 327 Election |

| Penalty-Free Access (<59½) | No (10% Penalty) | Yes (Death Distribution) | Yes (Death Distribution) |

| RMD Start Date | Sarah’s Age 75 | Michael’s Age 75 | Michael’s Age 75 |

| RMD Table Used | Uniform Lifetime (Favorable) | Single Life (Less Favorable) | Uniform Lifetime (Favorable) |

| Best For | Max Deferral, No Need for Cash | Need Cash Now | Need Cash Now + Lower Future RMDs |

Strategic Recommendation: For Sarah’s situation – a younger spouse who needs some liquidity now but wants long-term tax efficiency – the Section 327 election is the clear winner. She gets penalty-free access to funds immediately while preserving the favorable Uniform Lifetime Table for future RMDs. She can also choose to roll the account over to her own IRA later, once she passes age 59½, to further delay RMDs to her own age 75.

Case Study: The Successor Beneficiary Trap

This scenario often surprises families: what happens when a beneficiary dies before fully distributing the inherited IRA?

The Original Inheritance: Arthur died in 2018 (before the SECURE Act took effect). His wife Martha inherited his IRA and treated it as her own through a spousal rollover. Under the old rules, this was smart planning.

The Second Death: Martha dies in 2024 at age 77 (after her Required Beginning Date). Their son Greg, age 45, is named as the beneficiary.

What Happens to Greg?

When a beneficiary dies, the “Successor Beneficiary” rules kick in, and they’re not favorable.

The Stretch Ends Immediately: Greg cannot continue any stretch that Martha might have been using. The multi-generational deferral strategy dies with Martha.

Greg Gets the 10-Year Rule: As the successor beneficiary, Greg is subject to the 10-year liquidation requirement. He must empty the account by December 31, 2034.

But Wait – There’s More: Because Martha was treating the IRA as her own and died after her RBD, Greg must ALSO take annual RMDs in years 1-9.

The Annual RMD Calculation Twist

This is where it gets technical. Greg’s annual RMDs are based on Martha’s remaining life expectancy (not his own), using the “ghost” method:

Step 1: Determine what Martha’s life expectancy factor would have been in the year of her death (2024) at age 77. Using the Single Life Table, that’s approximately 13.0.

Step 2: For 2025 (Year 1 after death), subtract 1.0: Factor = 12.0

Step 3: Each subsequent year, continue subtracting 1.0:

- 2026: Factor = 11.0

- 2027: Factor = 10.0

- And so on…

Step 4: Calculate annual RMDs using these factors through 2033 (Year 9).

Step 5: By December 31, 2034 (Year 10), withdraw the entire remaining balance.

The Missed Planning Opportunity

If Martha had kept the original inherited IRA in beneficiary status instead of treating it as her own, the rules might have been different (though still complex). The key lesson: spousal rollovers, while beneficial for the surviving spouse, can create complications for the next generation under post-SECURE rules.

Strategic Takeaway

For families with significant IRA assets, it’s crucial to consider not just the first beneficiary’s situation, but also what happens at the second death. The old “stretch IRA” planning that worked across multiple generations is essentially dead. Modern planning requires thinking through the full succession chain.

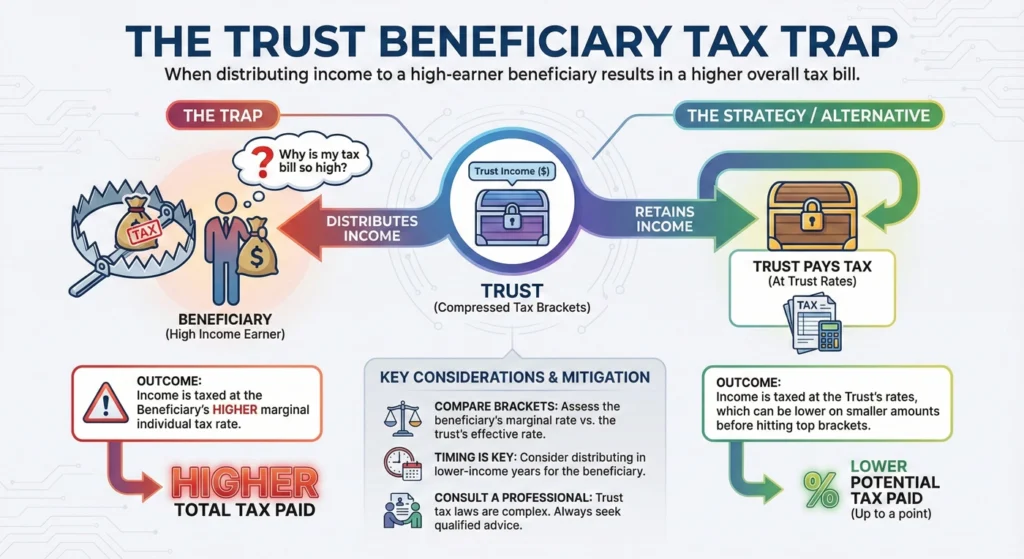

Case Study: The Trust Beneficiary Tax Trap

Not all inherited IRAs go directly to individuals. Sometimes they’re left to trusts, particularly for controlling assets distributed to young or potentially irresponsible heirs. However, the SECURE Act created a massive tax problem for certain types of trusts.

Meet Thomas, who left his IRA to “The Thomas Family Trust” with three adult children as beneficiaries. The trust is a valid “see-through” trust, so the IRS looks through to the underlying beneficiaries. Since they’re all adults, they’re NEDBs subject to the 10-year rule.

But the trust type matters tremendously:

Type A: Conduit Trust

How it works: The trust is required to immediately distribute all IRA withdrawals to the children.

Tax Impact: Income is taxed at the children’s individual tax rates (probably 22% or 24% for most middle-class beneficiaries).

The Problem: The trust offers little asset protection since everything flows through to the children within 10 years anyway.

Type B: Accumulation Trust (The Tax Disaster)

How it works: The trustee has discretion to retain distributions inside the trust, protecting the money from creditors or the beneficiaries’ poor spending decisions.

Tax Impact: This is where things go horribly wrong.

In 2024, trusts hit the top marginal tax bracket (37%) at just $15,200 of income. Compare this to an individual single filer who doesn’t hit 37% until taxable income exceeds $609,350.

The Math:

- $1M IRA emptied over 10 years = roughly $100,000/year

- Nearly the entire amount gets taxed at 37% + 3.8% Net Investment Income Tax = 40.8%

- Total tax: approximately $400,000+

If distributed to the children instead:

- Same $100,000/year split three ways = $33,333 each

- Likely taxed at 22% or 24%

- Total tax: approximately $220,000-240,000

- Tax Savings: $160,000-180,000

The Strategic Problem

Many accumulation trusts were drafted pre-SECURE Act assuming a 40-year distribution window with small annual income. Under the 10-year rule, they’ve become tax nightmares.

What to Do: Trustees should explore whether the trust document allows “sprinkling” distributions to beneficiaries to avoid these punitive trust tax rates. If the trust language permits it, distributing income to beneficiaries (effectively converting to conduit-like behavior) can save hundreds of thousands in taxes.

See-Through Trust Requirements

To qualify for any designated beneficiary treatment (even the 10-Year Rule), the trust must be a “See-Through” trust:

- Valid under state law

- Irrevocable upon death

- Beneficiaries must be identifiable

- Documentation provided to the custodian by October 31 of the year following death

If a trust fails these tests, it’s treated as a Non-Designated Beneficiary, triggering the 5-Year Rule or Ghost Rule—even worse outcomes.

Special Considerations for Inherited Roth IRAs

Now let’s talk about Roth IRAs for a second, because these are actually the best type of IRA to inherit (if you get to choose, which you don’t, but still).

The beautiful thing about an inherited Roth IRA is that all your distributions are completely tax-free, assuming the Roth was held for at least five years. We’re talking about the growth, the earnings, everything – totally tax-free. That’s a pretty amazing deal when you think about it.

The interesting part? Inherited Roth IRAs don’t require annual RMDs, regardless of how old the owner was when they died. But – and this is important – NEDBs still have to empty the account by the end of Year 10.

So what’s the smart play here? If you’re an NEDB with an inherited Roth IRA, leave that money alone as long as possible. Let it grow tax-free for the entire decade, then take it all out in Year 10. That way, you maximize the tax-free growth potential. It’s like getting free money from the investment gods.

Example: A $500,000 inherited Roth IRA growing at 7% annually would be worth nearly $1,000,000 after 10 years. The beneficiary withdraws that entire $1M with zero tax liability. That’s $500,000 of completely tax-free growth.

Simplifying RMD Compliance

Look, I get it—RMDs are complicated, they’re constantly changing, and the penalties for screwing them up are no joke. But the bottom line is this: with a little planning and the right strategies, you can make RMDs work for you instead of against you.

The key takeaways:

- Know when you need to start (age 73 currently, moving to 75 in 2033)

- Understand how to calculate RMD for IRA accounts using the right life expectancy table

- Don’t miss your deadlines (April 1st for the first one, December 31st for all others)

- Consider smart strategies like QCDs if you’re charitably inclined

- Use an RMD calculator for IRA accounts to double-check your math

- Keep good records and stay on top of new rules

- For inherited IRAs, understand whether annual RMDs are required based on when the original owner died

Because of all the moving parts—your age, your beneficiary’s age, recent legislation, inherited IRA rules—I strongly recommend sitting down with a CPA or financial advisor at least once to make sure you’ve got your ducks in a row. Most major brokerage firms like Schwab, Fidelity, or Vanguard offer free RMD calculators and even advisor consultations if you need them.

RMDs might not be the most exciting part of retirement planning (let’s be honest, they’re probably the least exciting), but getting them right means you keep more of your hard-earned money and avoid nasty surprises from the IRS. And that’s something we can all get behind!

The case studies we’ve explored—from Margaret’s straightforward first RMD calculation, to David inheriting from his mother with annual requirements, to Lily’s two-phase journey as a minor, to Sarah’s strategic spousal election options, to the successor beneficiary trap with Greg, to the trust taxation disaster—all illustrate that personalized planning is essential in the post-SECURE Act world.

Stay smart out there, and remember—when in doubt, ask for help. Your future self (and your tax bill) will thank you.

References

- Internal Revenue Service. (2024). Final Regulations on Required Minimum Distributions. Federal Register, Vol. 89, No. 141. Treasury Decision 10000. July 2024.

- Internal Revenue Service. (2024). Notice 2024-35: Waiver of Certain Required Minimum Distribution Penalties for 2024. IRS Notice 2024-35. April 2024.

- Internal Revenue Service. (2023). Notice 2023-54: Waiver of Certain Required Minimum Distribution Penalties for 2023. IRS Notice 2023-54. July 2023.

- Internal Revenue Service. (2022). Notice 2022-53: Waiver of Certain Required Minimum Distribution Penalties for 2021 and 2022. IRS Notice 2022-53. October 2022.

- Internal Revenue Service. (2022). Proposed Regulations on Required Minimum Distributions. Federal Register, Vol. 87, No. 40. Proposed Rule REG-105954-20. February 2022.

- U.S. Congress. (2022). SECURE 2.0 Act of 2022. Division T of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023. H.R. 2617, 117th Congress. Pub. L. No. 117-328. December 29, 2022.

- Internal Revenue Service. (2024). IRS Publication 590-B: Distributions from Individual Retirement Arrangements (IRAs). Department of the Treasury. Revised 2024.

- U.S. Congress. (2019). Setting Every Community Up for Retirement Enhancement (SECURE) Act of 2019. Division O of the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020. H.R. 1865, 116th Congress. Pub. L. No. 116-94. December 20, 2019.

- Internal Revenue Code. Section 401(a)(9): Required Minimum Distributions. 26 U.S.C. § 401(a)(9).

- Internal Revenue Code. Section 72(t): Additional Tax on Early Distributions from Qualified Retirement Plans. 26 U.S.C. § 72(t).

- Internal Revenue Service. (2024). Single Life Expectancy Table (Table I). Appendix B of IRS Publication 590-B. Effective for distributions beginning in 2022.

- Internal Revenue Service. (2024). Uniform Lifetime Table (Table III). Appendix B of IRS Publication 590-B. Effective for distributions beginning in 2022.

- Internal Revenue Service. (2024). Joint and Last Survivor Table (Table II). Appendix B of IRS Publication 590-B. Effective for distributions beginning in 2022.

- Internal Revenue Code. Section 641-643: Taxation of Trusts and Estates. 26 U.S.C. §§ 641-643.

- Internal Revenue Code. Section 4974: Excise Tax on Certain Accumulations in Qualified Retirement Plans. 26 U.S.C. § 4974.

- Internal Revenue Service. (2024). Form 5329: Additional Taxes on Qualified Plans (Including IRAs) and Other Tax-Favored Accounts. Department of the Treasury. Revised 2024.

- Internal Revenue Service. (2024). Form 8606: Nondeductible IRAs. Department of the Treasury. Revised 2024.

- Internal Revenue Code. Section 408A: Roth IRAs. 26 U.S.C. § 408A.

- Internal Revenue Code. Section 408: Individual Retirement Accounts. 26 U.S.C. § 408.

- Internal Revenue Code. Section 170(b)(1)(G): Qualified Charitable Distributions. 26 U.S.C. § 170(b)(1)(G).

- Congressional Research Service. (2020). The SECURE Act: Changes to Individual Retirement Accounts and Defined Contribution Plans. CRS Report R46342. January 2020.

- Joint Committee on Taxation. (2019). Estimated Budget Effects of the Revenue Provisions Contained in the SECURE Act. JCX-44-19. December 2019.

- American Bar Association. (2023). Estate Planning Implications of the SECURE Act and SECURE 2.0. Section of Real Property, Trust and Estate Law. May 2023.

- Treasury Regulations. §1.401(a)(9)-5: Required Minimum Distributions from Defined Contribution Plans. 26 CFR § 1.401(a)(9)-5.

- U.S. Congress. (2022). SECURE 2.0 Act of 2022, Section 327: Treatment of Certain Surviving Spouses. Division T of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023. H.R. 2617, 117th Congress. Pub. L. No. 117-328. December 29, 2022.

- Treasury Regulations. §1.401(a)(9)-4: Determination of the Designated Beneficiary. 26 CFR § 1.401(a)(9)-4.

- Internal Revenue Code. Section 401(a)(9)(B)(i): At Least As Rapidly (ALAR) Rule. 26 U.S.C. § 401(a)(9)(B)(i).

- Internal Revenue Service. (2024). Treatment of Minor Children as Eligible Designated Beneficiaries. Treasury Decision 10000, Section 1.401(a)(9)-4(e)(1). July 2024.

- Treasury Regulations. §1.401(a)(9)-8: Special Rules for Qualified Trusts. 26 CFR § 1.401(a)(9)-8.

- Internal Revenue Service. (2024). Successor Beneficiary Rules and the Termination of Stretch Provisions. Treasury Decision 10000, Section 1.401(a)(9)-5(f). July 2024.

- Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA). (2024). Inherited IRAs: Understanding Your Distribution Options. FINRA Investor Education. Updated March 2024.

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. (2022). Retirement Security: Federal Action Needed to Clarify Tax Treatment of Inherited IRAs. GAO-22-104541. March 2022.

- Internal Revenue Service. (2024). Frequently Asked Questions about Required Minimum Distributions. IRS.gov. Updated January 2025.

- American Institute of Certified Public Accountants. (2024). SECURE 2.0 Tax Planning Guide for Practitioners. AICPA Tax Section. February 2024.

- National Association of Estate Planners & Councils. (2023). Best Practices for Post-SECURE Act Beneficiary Designations. NAEPC Journal of Estate & Tax Planning. Volume 49, Issue 3. September 2023.

- Treasury Regulations. §1.408-8: Distribution Requirements for Individual Retirement Plans. 26 CFR § 1.408-8.

Additional Resources

IRS Official Resources

- IRS Publication 590-B (Distributions from Individual Retirement Arrangements): www.irs.gov/publications/p590b

- IRS Required Minimum Distribution Worksheets: www.irs.gov/retirement-plans/plan-participant-employee/required-minimum-distributions

- IRS Notice 2024-35 (Full Text): www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/n-24-35.pdf

- IRS Life Expectancy Tables: www.irs.gov/retirement-plans/plan-participant-employee/retirement-topics-required-minimum-distributions-rmds

Legislative Texts

- SECURE Act of 2019 (Full Text): www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/1865

- SECURE 2.0 Act of 2022 (Full Text): www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/2617

Professional Organizations

- American Bar Association – Real Property, Trust and Estate Law Section: www.americanbar.org/groups/real_property_trust_estate

- American Institute of Certified Public Accountants – Tax Section: www.aicpa.org/tax

- National Association of Estate Planners & Councils: www.naepc.org

Calculation Tools

Joint and Last Survivor Table: Available in IRS Publication 590-B, Appendix B

IRS RMD Comparison Chart: www.irs.gov/retirement-plans/plan-participant-employee/retirement-topics-beneficiary

Single Life Expectancy Table: Available in IRS Publication 590-B, Appendix B

Uniform Lifetime Table: Available in IRS Publication 590-B, Appendix B