Okay, so here’s the deal – if you’ve inherited an IRA recently, 2025 is kind of a big year for you. Like, circle-it-on-your-calendar-with-a-red-marker big. And honestly, I know dealing with Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs) sounds about as fun as doing your taxes on a Saturday night, but trust me, you’re going to want to pay attention to this one.

So what exactly are RMDs? Think of them as Uncle Sam’s way of saying, “Hey, you’ve enjoyed tax-deferred growth on that retirement money long enough – now it’s time to pay the piper.” Basically, they’re mandatory annual withdrawals from tax-deferred retirement accounts like traditional IRAs. The government wants its cut, and RMDs are how they make sure they get it.

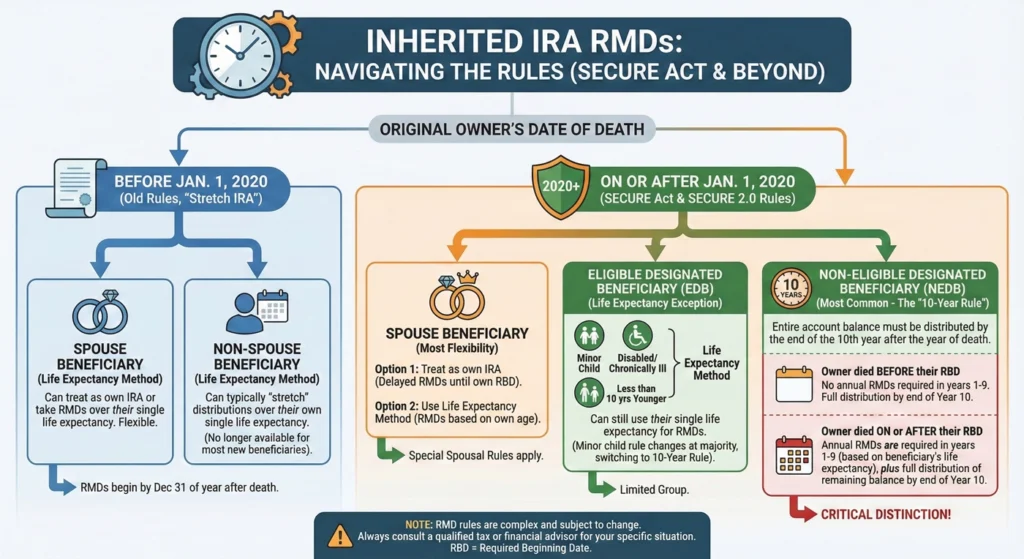

Now, here’s where things get interesting (and by interesting, I mean potentially expensive if you don’t pay attention). The rules around inherited IRAs have completely changed thanks to two pieces of legislation: the SECURE Act of 2019 and the SECURE 2.0 Act of 2022. These acts didn’t just tweak things a little – they basically rewrote the playbook. The original IRA owner’s RMD age got bumped up to 73, and inheritance rules? Yeah, those got a serious makeover.

But here’s the kicker – 2025 is when the IRS stops being Mr. Nice Guy. They’ve been giving people a pass for the last few years while they figured out all the details, but starting this year, they’re actually enforcing the new RMD requirements for inherited IRAs received after December 31, 2019. And the penalties? Let’s just say they’re not something you want to mess around with.

- The Paradigm Shift: From "Stretch IRA" to the 10-Year Rule

- Unpacking the Two Critical 10-Year Rule Scenarios (Post-2020 Deaths)

- Real-World Case Study: The Adult Child (NEDB)

- Strategic Planning by Beneficiary Category

- Case Study: The Younger Surviving Spouse and SECURE 2.0

- Case Study: The Minor Child's Two-Phase Journey

- Case Study: The Trust Beneficiary Tax Trap

- Special Considerations for Inherited Roth IRAs

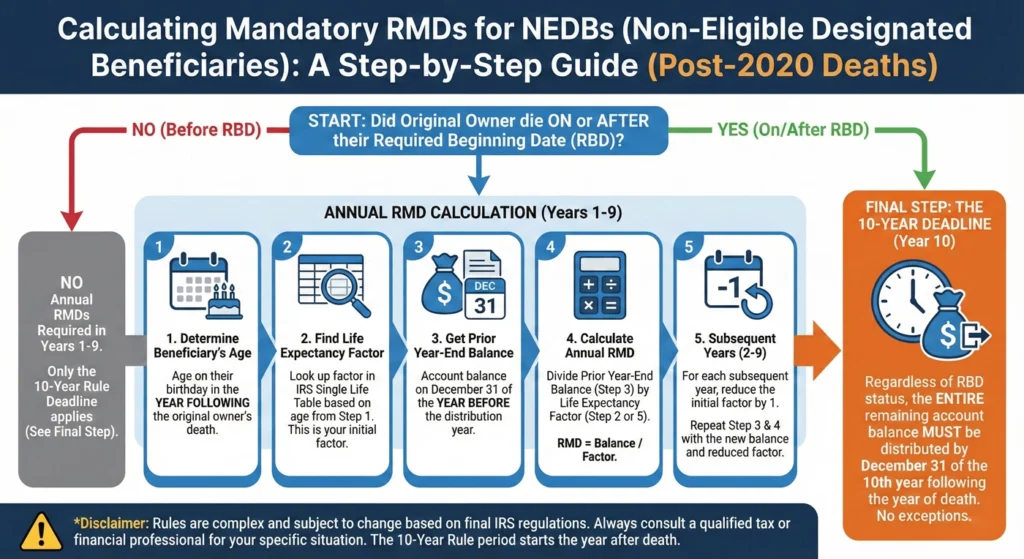

- Calculating Mandatory RMDs for NEDBs (Step-by-Step Guide)

- Actionable Strategies to Minimize Tax Impact

- Conclusion: The Importance of Proactive Planning

The Paradigm Shift: From “Stretch IRA” to the 10-Year Rule

Remember the good old days? Okay, maybe you don’t, but before 2020, inheriting an IRA was actually pretty sweet. You could do what people called a “stretch IRA,” which meant you could spread those RMDs out over your entire lifetime. It was like winning the slow-and-steady financial planning lottery – decades of tax-deferred growth and tiny, manageable distributions.

Well, I hate to be the bearer of bad news, but those days are pretty much over for most people.

Enter the 10-Year Rule, stage left. If you’re a non-spouse beneficiary who inherited an IRA after January 1, 2020, you’ve got a decade to drain that account completely. Yep, by December 31 of the tenth year following the original owner’s death, that entire inherited IRA needs to be at zero. No more stretching it out until you’re 90 and using it as a steady income stream.

Now, here’s where the IRS actually showed a little mercy (shocking, I know). While they were getting their ducks in a row and finalizing all the regulations, they waived RMD penalties from 2020 through 2024. Basically, they were like, “We know this is confusing, so we won’t penalize you while we figure it out ourselves.” But that grace period? It’s over. Done. Finito.

And if you don’t take your required withdrawal starting in 2025? You’re looking at a potential excise tax of 25% of whatever you should have withdrawn. That’s not a typo – twenty-five percent! Though if you catch it quickly and fix it, they might reduce it to 10%. But still, who wants to voluntarily give the IRS an extra 10% of their money?

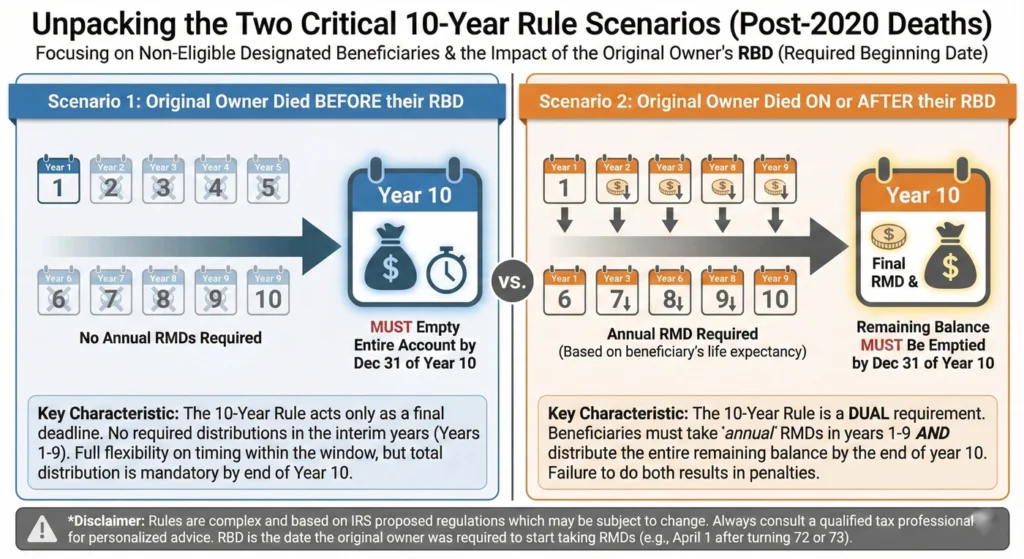

Unpacking the Two Critical 10-Year Rule Scenarios (Post-2020 Deaths)

Alright, this is where it gets a bit tricky, but stick with me because understanding this could literally save you thousands of dollars. The 10-year rule isn’t one-size-fits-all – there are actually two different scenarios depending on when the original owner died in relation to their own RMDs.

Scenario 1: Owner Died After Starting RMDs (Post-RBD)

Let’s say the original IRA owner had already started taking their own RMDs when they passed away (that’s after their Required Beginning Date or RBD, for those keeping score at home). In this case, you’re not just on the hook for cleaning out the account by Year 10 – you also have to take annual RMDs in Years 1 through 9.

Here’s how it works: You calculate your annual RMD based on your own single life expectancy. The IRS has this fun little table that tells you what your life expectancy factor is based on your age. Then, you take the account balance from December 31 of the previous year and divide it by that factor. Boom – that’s your RMD for the year.

But here’s the kicker – even though you’re taking these annual distributions, you still have to completely empty the account by the end of Year 10. So you could end up with this massive “balloon payment” in that final year, which could be a real tax headache if you’re not careful.

Scenario 2: Owner Died Before Starting RMDs (Pre-RBD)

Now, if the original owner died before they had to start taking their own RMDs, you catch a bit of a break. You still have to empty the account by the end of Year 10, but you don’t have required annual distributions during Years 1 through 9.

This gives you way more flexibility. You can take out a little, a lot, or nothing at all in those first nine years – it’s totally up to you and your tax situation. Just don’t forget about that Year 10 deadline, because when it hits, everything’s got to come out.

Real-World Case Study: The Adult Child (NEDB)

Let me bring this to life with a real example. Meet Robert Smith, age 50, who inherited his father Arthur’s $1,000,000 Traditional IRA in June 2022. Robert is what the IRS calls a Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary (NEDB) – basically an adult child subject to the 10-year rule.

But here’s where things get interesting: the rules Robert has to follow depend entirely on how old his father was when he died.

If Arthur Died Before His RBD (Age 68)

Arthur was born in 1954, so his Required Beginning Date would have been at age 73 (in 2028). Since he died at 68, he died before his RBD.

What this means for Robert: He’s subject to the 10-year rule WITHOUT annual RMDs. The 10-year window runs from January 1, 2023 through December 31, 2032. Robert has total flexibility over when to take distributions during this period.

Option A (Maximum Deferral): Robert could take $0 in years 2023-2031, letting the account grow tax-deferred. Assuming a 6% return, that $1M could grow to approximately $1.79M by 2032. But here’s the catch – withdrawing $1.79M in a single year would slam him into the highest tax bracket (37%+) plus potentially the 3.8% Net Investment Income Tax.

Option B (Smart Tax Management): Robert could withdraw roughly $135,000 annually to fill lower tax brackets (like the 22% or 24% bracket), avoiding that massive tax bomb in year 10.

If Arthur Died After His RBD (Age 79)

Now let’s say Arthur was born in 1943 and reached his RBD back in 2014 at age 70½. He died at 79, well after his RBD started.

What this means for Robert: He’s subject to the 10-year rule WITH annual RMDs. This is where things get more complicated.

The Good News: Thanks to IRS Notice 2024-35, Robert didn’t face penalties for skipping RMDs in 2023 and 2024 during the transition period. He doesn’t need to make up those missed distributions.

The Bad News: Starting in 2025, Robert MUST take annual RMDs. Here’s how it works:

Step 1: In the year following Arthur’s death (2023), Robert turned 51. Looking at the IRS Single Life Expectancy Table, the factor for age 51 is 35.3.

Step 2: For each subsequent year, subtract 1.0:

- 2023 Factor: 35.3 (Waived)

- 2024 Factor: 34.3 (Waived)

- 2025 Factor: 33.3 (First Mandatory Distribution)

- 2026 Factor: 32.3

- And so on…

Step 3: Calculate the 2025 RMD. If the account balance on December 31, 2024 is $1,100,000:

- RMD = $1,100,000 ÷ 33.3 = $33,033.03

Step 4: Continue this calculation each year through 2031 (Year 9).

Step 5: By December 31, 2032 (Year 10), withdraw the entire remaining balance, regardless of what the RMD calculation says.

The Strategic Problem: Those annual RMDs (roughly 3% per year) won’t deplete the account significantly. It will likely continue growing, leaving Robert with a substantial balloon payment in 2032. He should probably withdraw more than the minimum each year to manage his tax liability efficiently.

Strategic Planning by Beneficiary Category

Not everyone’s in the same boat when it comes to inherited IRA rules. The IRS created different categories of beneficiaries, and honestly, some people got a way better deal than others. Let’s break it down.

Surviving Spouses (Maximum Flexibility)

If you inherited your spouse’s IRA, congratulations – you basically hit the beneficiary jackpot. Spouses get the most favorable treatment and aren’t stuck with that 10-year rule everyone else is dealing with.

You’ve got three main options here:

First, you can treat the IRA as your own through a spousal rollover. This is huge because it means your RMDs are based on your age, not your deceased spouse’s age. So if you’re younger, you can delay taking distributions until your own RBD rolls around, letting that money continue to grow tax-deferred.

Second, you can keep it as an inherited IRA and remain as a beneficiary. This sounds less appealing at first, but it actually makes a lot of sense if you’re under 59½. Why? Because if you need to access the funds, you can take them out penalty-free. Normally, withdrawing from an IRA before 59½ hits you with a 10% early withdrawal penalty, but inherited IRAs are exempt from that.

The right choice really depends on how old you are compared to your spouse and whether you need access to the money right now. If you’re sitting pretty financially and can let it grow, the rollover is usually the way to go. If you need the funds sooner, keeping it as an inherited IRA might be smarter.

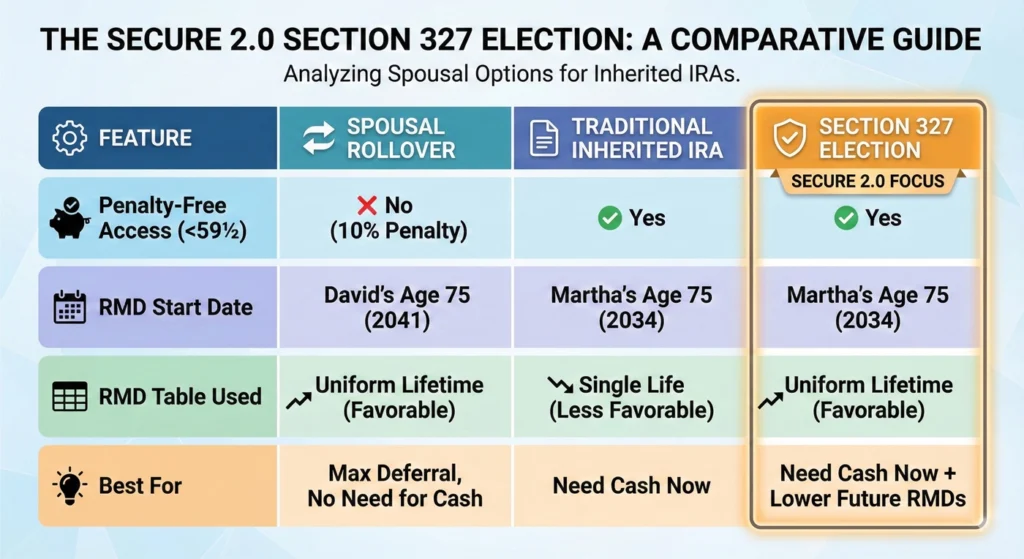

Case Study: The Younger Surviving Spouse and SECURE 2.0

Let me introduce you to David Jones, age 58, who inherited his wife Martha’s $2,000,000 Traditional IRA in 2024. Martha died at age 65 – before her Required Beginning Date (which would have been age 75). David is under age 59½, which creates a specific planning opportunity thanks to SECURE 2.0.

Option 1: Traditional Spousal Rollover

David could roll the IRA into his own name.

Pros:

- RMDs are delayed until David reaches age 75 (in 2041) – maximum tax deferral

- Once RMDs begin, he uses the Uniform Lifetime Table, which results in smaller distributions than the Single Life Table

Cons:

- If David needs money before age 59½, he’ll face the 10% early withdrawal penalty

- This could be devastating if he has unexpected expenses

Option 2: Traditional Inherited IRA

David keeps the account as an Inherited IRA in beneficiary status.

Pros:

- All distributions are penalty-free, regardless of David’s age – critical for liquidity

Cons:

- RMDs would have to start when Martha would have reached age 75 (2034)

- He’d be forced to use the Single Life Table, resulting in larger required distributions than the Uniform Table

Option 3: The SECURE 2.0 Section 327 Election (The Game Changer)

Here’s where things get really interesting. Under SECURE 2.0’s Section 327, David can elect to be treated as the deceased employee for RMD purposes.

How it works:

- The account remains an Inherited IRA (so distributions stay penalty-free)

- But RMD rules apply as if David were Martha

- RMDs are delayed until Martha would have reached age 75 (2034)

- The Big Win: David gets to use the Uniform Lifetime Table (based on his age) to calculate RMDs once they begin

The Result: David gets the best of both worlds – penalty-free access to cash if needed before age 59½, PLUS the favorable lower RMDs of the Uniform Lifetime Table.

Here’s a quick comparison:

| Feature | Spousal Rollover | Traditional Inherited IRA | Section 327 Election |

| Penalty-Free Access (<59½) | No (10% Penalty) | Yes | Yes |

| RMD Start Date | David’s Age 75 (2041) | Martha’s Age 75 (2034) | Martha’s Age 75 (2034) |

| RMD Table Used | Uniform Lifetime (Favorable) | Single Life (Less Favorable) | Uniform Lifetime (Favorable) |

| Best For | Max Deferral, No Need for Cash | Need Cash Now | Need Cash Now + Lower Future RMDs |

Strategic Recommendation: For David’s situation – a younger spouse who might need access to funds before 59½ – the Section 327 election is the clear winner. He can also choose to roll the account over to his own IRA later, once he passes age 59½, to further delay RMDs to his own age 75.

Eligible Designated Beneficiaries (EDBs)

So there are some people who get to escape the 10-year rule entirely, and they’re called Eligible Designated Beneficiaries, or EDBs for short. Lucky them, right?

Who makes the cut? Well, surviving spouses (as we just covered), minor children of the deceased (though only until they hit the age of majority, which is usually 21), disabled or chronically ill individuals who meet the IRS’s strict definitions, and anyone who’s not more than 10 years younger than the person who died.

That last one’s interesting – so if your older brother left you his IRA and you’re only eight years younger, you qualify as an EDB. But if your uncle who’s 20 years older than you leaves you his IRA? Nope, you’re out of luck.

The big advantage here is that EDBs can often still use that lifetime “stretch” approach based on their own life expectancy. It’s like they got grandfathered into the old rules, which is pretty sweet for tax planning purposes.

Case Study: The Minor Child’s Two-Phase Journey

Here’s a complex scenario that catches many families off guard. Sarah Lee died in 2024, leaving her $500,000 Traditional IRA to her 10-year-old daughter Jennifer. As a minor child of the account owner, Jennifer qualifies as an Eligible Designated Beneficiary – but only temporarily.

Phase 1: Ages 10-21 (The EDB Years)

Jennifer must take annual RMDs based on her Single Life Expectancy starting in 2025 (the year following Sarah’s death).

The Calculation:

- Jennifer turns 11 in 2025

- IRS Single Life Table Factor for Age 11 is 73.9

- 2025 RMD: $500,000 ÷ 73.9 = $6,765.90

This represents only about 1.3% of the account, allowing substantial continued growth during Jennifer’s childhood. Each year, the factor decreases by 1.0.

Important Note: The IRS standardized the “age of majority” at 21 for everyone, regardless of state laws. This extends the EDB period for children in states with lower ages of majority (like 18).

Phase 2: The Transition at Age 21 (Year 2035)

When Jennifer turns 21 in 2035, everything changes. She immediately loses her EDB status and becomes a Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary.

The 10-Year Clock Starts: The 10-year liquidation period begins January 1, 2036 (the year after she reaches age 21) and ends December 31, 2045 (when she turns 31).

Phase 3: Ages 21-31 (The 10-Year Rule)

During this window (2036-2045), Jennifer must:

- Continue taking annual RMDs based on her life expectancy (since she was already taking distributions as a minor)

- Completely liquidate the account by December 31, 2045

The Critical Compliance Point: Custodians must rigorously track that 21st birthday. Missing the transition from the “Stretch” calculation to the “10-Year Liquidation” schedule could result in massive penalties – 25% (or 10% if corrected quickly) of the amounts that should have been withdrawn.

The Big Picture: Jennifer gets 21 years of favorable stretch treatment, then faces a 10-year liquidation window. By age 31, the inherited IRA must be completely empty.

Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries (NEDBs)

And then there’s everyone else – the Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiaries, or NEDBs. This is probably most people reading this who’ve inherited an IRA from a parent, sibling, friend, or other relative.

If you’re an NEDB, you’re playing by the strict 10-year rule. And if the original owner died after they’d already started taking their RMDs, you’ve got those annual distribution requirements in Years 1 through 9, too. No exceptions, no special treatment, no fun.

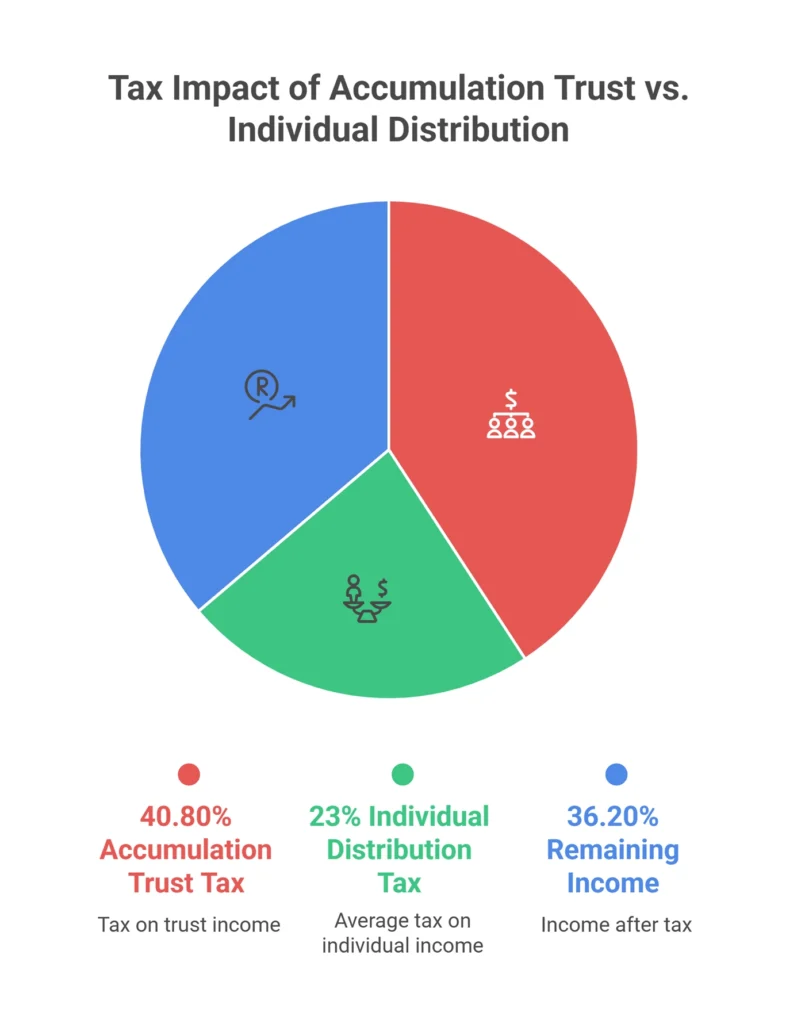

Case Study: The Trust Beneficiary Tax Trap

Not all inherited IRAs go directly to individuals. Sometimes they’re left to trusts, particularly for controlling assets distributed to young or potentially irresponsible heirs. But the SECURE Act created a massive tax problem for certain types of trusts.

Meet Thomas, who left his IRA to “The Thomas Family Trust” with three adult children as beneficiaries. The trust is a valid “see-through” trust, so the IRS looks through to the underlying beneficiaries. Since they’re all adults, they’re NEDBs subject to the 10-year rule.

But here’s where the trust type matters tremendously:

Not all inherited IRAs go directly to individuals. Sometimes they’re left to trusts, particularly for controlling assets distributed to young or potentially irresponsible heirs. But the SECURE Act created a massive tax problem for certain types of trusts.

Meet Thomas, who left his IRA to “The Thomas Family Trust” with three adult children as beneficiaries. The trust is a valid “see-through” trust, so the IRS looks through to the underlying beneficiaries. Since they’re all adults, they’re NEDBs subject to the 10-year rule.

But here’s where the trust type matters tremendously:

Type A: Conduit Trust

How it works: The trust is required to immediately distribute all IRA withdrawals to the children.

Tax Impact: Income is taxed at the children’s individual tax rates (probably 22% or 24% for most middle-class beneficiaries).

The Problem: The trust offers little asset protection since everything flows through to the children within 10 years anyway.

Type B: Accumulation Trust (The Tax Disaster)

How it works: The trustee has discretion to retain distributions inside the trust, protecting the money from creditors or the beneficiaries’ poor spending decisions.

Tax Impact: This is where things go horribly wrong.

In 2024, trusts hit the top marginal tax bracket (37%) at just $15,200 of income. Compare this to an individual single filer who doesn’t hit 37% until taxable income exceeds $609,350.

The Math:

- $1M IRA emptied over 10 years = roughly $100,000/year

- Nearly the entire amount gets taxed at 37% + 3.8% Net Investment Income Tax = 40.8%

- Total tax: approximately $400,000+

If distributed to the children instead:

- Same $100,000/year split three ways = $33,333 each

- Likely taxed at 22% or 24%

- Total tax: approximately $220,000-240,000

- Tax Savings: $160,000-180,000

The Strategic Problem: Many accumulation trusts were drafted pre-SECURE Act assuming a 40-year distribution window with small annual income. Under the 10-year rule, they’ve become tax nightmares.

What to Do: Trustees should explore whether the trust document allows “sprinkling” distributions to beneficiaries to avoid these punitive trust tax rates. If the trust language permits it, distributing income to beneficiaries (effectively converting to conduit-like behavior) can save hundreds of thousands in taxes.

Special Considerations for Inherited Roth IRAs

Now let’s talk about Roth IRAs for a second, because these are actually the best type of IRA to inherit (if you get to choose, which you don’t, but still).

The beautiful thing about an inherited Roth IRA is that all your distributions are completely tax-free, assuming the Roth was held for at least five years. We’re talking about the growth, the earnings, everything – totally tax-free. That’s a pretty amazing deal when you think about it.

Here’s the interesting part: inherited Roth IRAs don’t require annual RMDs, regardless of how old the owner was when they died. But – and this is important – NEDBs still have to empty the account by the end of Year 10.

So what’s the smart play here? If you’re an NEDB with an inherited Roth IRA, leave that money alone as long as possible. Let it grow tax-free for the entire decade, then take it all out in Year 10. That way, you maximize the tax-free growth potential. It’s like getting free money from the investment gods.

Example: A $500,000 inherited Roth IRA growing at 7% annually would be worth nearly $1,000,000 after 10 years. The beneficiary withdraws that entire $1M with zero tax liability. That’s $500,000 of completely tax-free growth.

Calculating Mandatory RMDs for NEDBs (Step-by-Step Guide)

Okay, so if you’re an NEDB and the original owner died after starting their RMDs, you need to calculate your annual RMD. And here’s a fun fact – most custodians like Schwab, Fidelity, or Vanguard won’t do this calculation for you because it’s complicated. So grab your calculator (or an RMD calculator for inherited IRA), and let’s walk through this together.

Step 1: Find the Account’s Fair Market Value

Look at what the inherited IRA was worth on December 31 of the previous year. Most custodians will show you this on your statement, or you can log into your account online and find it.

Step 2: Determine Your Life Expectancy Factor

Head to the IRS website and find the Single Life Expectancy Table (it’s in Publication 590-B, if you want to sound fancy). Find your age in the year after the account owner died – that’s Year 1. The table will give you a life expectancy factor.

Step 3: Do the Math

This is where you calculate your RMD. Take the account balance from Step 1 and divide it by the life expectancy factor from Step 2. The formula looks like this:

RMD = Account Balance (December 31, Prior Year) ÷ Life Expectancy Factor

So if your account was worth $200,000 on December 31 and your life expectancy factor is 40, your RMD would be $5,000 for that year.

Step 4: Rinse and Repeat (With a Twist)

For each subsequent year (Years 2 through 9), you reduce your life expectancy factor by 1.0 from the previous year. So if it was 40 in Year 1, it’s 39 in Year 2, 38 in Year 3, and so on. Then you use the new December 31 account balance and the reduced factor to calculate that year’s RMD.

If you’re thinking, “This sounds complicated and I don’t want to mess it up,” you’re not alone. There are plenty of RMD calculators for inherited IRA online that can help, or better yet, work with a financial advisor or tax professional who can make sure you’re doing it right.

Actionable Strategies to Minimize Tax Impact

Let’s talk strategy, because just knowing the rules isn’t enough – you need to be smart about how to calculate RMD for inherited IRA and when to take your distributions to minimize your tax hit.

Manage Your Tax Brackets

If you’ve inherited a traditional IRA and you’re an NEDB, you’ve got some control over how much you withdraw each year (within the rules, of course). The key is to spread those withdrawals strategically across the 10-year period. Try to take distributions during years when your income is lower, so you don’t push yourself into a higher tax bracket.

For example, if you’re planning to take a sabbatical or semi-retire during that decade, those might be perfect years to take bigger distributions because your overall income will be lower. Conversely, if you get a big promotion or have a windfall year, maybe take just the minimum that year if you have flexibility.

Don’t Create a Year 10 Disaster

Here’s a mistake I see people make all the time – they put off thinking about their inherited IRA and then suddenly it’s Year 10 and they’ve got to take out this massive lump sum. If you’ve got a $500,000 inherited IRA and you wait until Year 10 to take it all, you could easily end up in the highest tax bracket. That’s like voluntarily giving the IRS an extra $100,000 or more. Ouch.

Instead, plan ahead. Even if you don’t have annual RMD requirements (Scenario 2), consider taking distributions throughout the decade to spread out the tax impact.

Consider Professional Help

Look, I’m all for DIY financial planning, but inherited IRAs are complex enough that it’s usually worth talking to a professional. Custodians typically don’t calculate RMDs for inherited IRAs because everyone’s situation is different, so you’re kind of on your own to figure it out.

A good tax advisor or financial planner can help you develop a withdrawal strategy that makes sense for your specific situation, considering your income, tax brackets, other retirement accounts, and overall financial goals. They can also help you avoid costly mistakes that could trigger penalties.

Think About Trusts (Carefully)

Some people inherit IRAs through trusts, or they’re considering using a trust for their own estate planning. Just be aware that trusts can face higher tax rates than individuals, so they’re not always the optimal solution. If you’re dealing with a trust situation, definitely get professional advice.

As we saw in the Thomas Family Trust case study, accumulation trusts can create tax disasters under the 10-year rule, potentially costing hundreds of thousands in unnecessary taxes compared to distributing directly to individual beneficiaries.

Conclusion: The Importance of Proactive Planning

Alright, let’s wrap this up with a call to action, because the worst thing you can do with an inherited IRA right now is nothing.

The new rules are definitely complex – I won’t sugarcoat that. Between the 10-year rule, the different beneficiary categories, the post-RBD versus pre-RBD scenarios, and the calculations involved, there’s a lot to keep track of. But here’s the good news: it’s totally manageable if you’re proactive about it.

Start by figuring out what type of beneficiary you are. Are you a surviving spouse with maximum flexibility? An Eligible Designated Beneficiary who can stretch distributions? Or a Non-Eligible Designated Beneficiary subject to the strict 10-year rule?

Next, confirm when the original owner died. Did they pass away before 2020 (old rules might still apply), or after December 31, 2019 (new rules are in effect)? And had they started taking their own RMDs yet?

If you’re required to take annual RMDs, don’t wait – calculate them and start withdrawing now. The 2025 penalties are no joke, and you don’t want to be scrambling at year-end trying to figure out how much you need to take.

Finally, think strategically about your withdrawals. Even if you’re not required to take annual distributions, it often makes sense to spread out your withdrawals over the decade to manage your tax liability. That Year 10 deadline is going to come faster than you think, and you don’t want to be stuck with a massive tax bomb.

The bottom line? Inherited IRAs are valuable assets, but they come with strings attached. Take the time to understand the rules that apply to your situation, run the numbers (or use an RMD calculator for inherited IRA), and consider working with a professional to develop a smart withdrawal strategy. Your future self – and your tax bill – will thank you.

The case studies we’ve explored – from Robert’s $1M inheritance requiring careful tax bracket management, to David’s strategic use of the SECURE 2.0 election, to Jennifer’s two-phase journey from minor to adult, to the Thomas Family Trust’s tax disaster – all illustrate that one-size-fits-all approaches don’t work anymore. Your specific situation determines your optimal strategy.

And hey, if nothing else, at least you’re not dealing with the old rules, the new rules, and the transitional rules all at once anymore. Small victories, right?

Now go forth and conquer those RMDs! You’ve got this.

References

- Internal Revenue Service. (2024). Final Regulations on Required Minimum Distributions. Federal Register, Vol. 89, No. 141. Treasury Decision 10000. July 2024.

- Internal Revenue Service. (2024). Notice 2024-35: Waiver of Certain Required Minimum Distribution Penalties for 2024. IRS Notice 2024-35. April 2024.

- Internal Revenue Service. (2023). Notice 2023-54: Waiver of Certain Required Minimum Distribution Penalties for 2023. IRS Notice 2023-54. July 2023.

- Internal Revenue Service. (2022). Notice 2022-53: Waiver of Certain Required Minimum Distribution Penalties for 2021 and 2022. IRS Notice 2022-53. October 2022.

- Internal Revenue Service. (2022). Proposed Regulations on Required Minimum Distributions. Federal Register, Vol. 87, No. 40. Proposed Rule REG-105954-20. February 2022.

- U.S. Congress. (2022). SECURE 2.0 Act of 2022. Division T of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023. H.R. 2617, 117th Congress. Pub. L. No. 117-328. December 29, 2022.

- Internal Revenue Service. (2024). IRS Publication 590-B: Distributions from Individual Retirement Arrangements (IRAs). Department of the Treasury. Revised 2024.

- U.S. Congress. (2019). Setting Every Community Up for Retirement Enhancement (SECURE) Act of 2019. Division O of the Further Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2020. H.R. 1865, 116th Congress. Pub. L. No. 116-94. December 20, 2019.

- Internal Revenue Code. Section 401(a)(9): Required Minimum Distributions. 26 U.S.C. § 401(a)(9).

- Internal Revenue Code. Section 72(t): Additional Tax on Early Distributions from Qualified Retirement Plans. 26 U.S.C. § 72(t).

- Internal Revenue Service. (2024). Single Life Expectancy Table (Table I). Appendix B of IRS Publication 590-B. Effective for distributions beginning in 2022.

- Internal Revenue Service. (2024). Uniform Lifetime Table (Table III). Appendix B of IRS Publication 590-B. Effective for distributions beginning in 2022.

- Internal Revenue Code. Section 641-643: Taxation of Trusts and Estates. 26 U.S.C. §§ 641-643.

- Internal Revenue Code. Section 4974: Excise Tax on Certain Accumulations in Qualified Retirement Plans. 26 U.S.C. § 4974.

- Congressional Research Service. (2020). The SECURE Act: Changes to Individual Retirement Accounts and Defined Contribution Plans. CRS Report R46342. January 2020.

- Joint Committee on Taxation. (2019). Estimated Budget Effects of the Revenue Provisions Contained in the SECURE Act. JCX-44-19. December 2019.

- American Bar Association. (2023). Estate Planning Implications of the SECURE Act and SECURE 2.0. Section of Real Property, Trust and Estate Law. May 2023.

- Internal Revenue Code. Section 408: Individual Retirement Accounts. 26 U.S.C. § 408.

- Treasury Regulations. §1.401(a)(9)-5: Required Minimum Distributions from Defined Contribution Plans. 26 CFR § 1.401(a)(9)-5.

- Social Security Administration. (2024). Life Expectancy Calculators and Actuarial Tables. SSA Publication No. 11-11536. Revised 2024.

- Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA). (2024). Inherited IRAs: Understanding Your Distribution Options. FINRA Investor Education. Updated March 2024.

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. (2022). Retirement Security: Federal Action Needed to Clarify Tax Treatment of Inherited IRAs. GAO-22-104541. March 2022.

- Internal Revenue Service. (2024). Frequently Asked Questions about Required Minimum Distributions. IRS.gov. Updated January 2025.

- American Institute of Certified Public Accountants. (2024). SECURE 2.0 Tax Planning Guide for Practitioners. AICPA Tax Section. February 2024.

- National Association of Estate Planners & Councils. (2023). Best Practices for Post-SECURE Act Beneficiary Designations. NAEPC Journal of Estate & Tax Planning. Volume 49, Issue 3. September 2023.

- Internal Revenue Code. Section 408A: Roth IRAs. 26 U.S.C. § 408A.

- Treasury Regulations. §1.408-8: Distribution Requirements for Individual Retirement Plans. 26 CFR § 1.408-8.

Additional Resources

IRS Official Resources

- IRS Publication 590-B (Distributions from Individual Retirement Arrangements): www.irs.gov/publications/p590b

- IRS Required Minimum Distribution Worksheets: www.irs.gov/retirement-plans/plan-participant-employee/required-minimum-distributions

- IRS Notice 2024-35 (Full Text): www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/n-24-35.pdf

Legislative Texts

- SECURE Act of 2019 (Full Text): www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/1865

- SECURE 2.0 Act of 2022 (Full Text): www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/2617

Professional Organizations

- American Bar Association – Real Property, Trust and Estate Law Section: www.americanbar.org/groups/real_property_trust_estate

- American Institute of Certified Public Accountants – Tax Section: www.aicpa.org/tax

- National Association of Estate Planners & Councils: www.naepc.org

Calculation Tools

- IRS RMD Comparison Chart: www.irs.gov/retirement-plans/plan-participant-employee/retirement-topics-beneficiary

- Single Life Expectancy Table: Available in IRS Publication 590-B, Appendix B

- Uniform Lifetime Table: Available in IRS Publication 590-B, Appendix B