Okay, real talk – here we are in 2025, and weight loss is still one of those things everyone wants to figure out, right? But here’s the kicker: 83% of people trying to lose weight throw in the towel within the first month. Ouch.

And you know why? Because most folks are basically guessing their calorie deficit like they’re playing darts blindfolded. Spoiler alert: sustainable fat loss isn’t about having superhuman willpower – it’s actually about getting your math right. Wild, I know.

So here’s what we’re gonna do. I’m going to show you how to calculate calorie deficit the right way – none of that “eat 1200 calories and pray” nonsense. We’re talking evidence-based, dynamic calculations that’ll actually work without leaving you hangry, exhausted, or stuck on those annoying plateaus that make you want to rage-quit your diet.

Now, this is especially important if you’re a knowledge worker, digital creator (shoutout to my Roblox developers out there!), or competitive gamer. Getting your deficit wrong can literally tank your working memory by over 20% and make those bug fixes take 30% longer. Yeah, your brain runs on fuel, and if you cut it too aggressively, you’re basically trying to run Photoshop on a potato. Not ideal.

Let’s dive in.

- The Critical Flaw: Why Standard Calorie Deficit Approaches Fail

- Step 1: Establishing Your True Total Daily Energy Expenditure (TDEE)

- Step 2: Calculating Your Optimal, Personalized Deficit

- Advanced Strategies: Dynamic Adjustments and Metabolic Safeguards

- Beyond Calories: Supporting Sustainability and Mental Health

- Conclusion: Systems, Not Willpower

The Critical Flaw: Why Standard Calorie Deficit Approaches Fail

The Hidden Reality of Maintenance Miscalculations

Alright, so here’s where things get messy. Most people start their weight loss journey by completely botching their baseline numbers. I’m talking 76% of dieters underestimate their maintenance calories by 300–500 calories. That’s like… a whole meal you didn’t account for.

And then there’s the opposite problem – some people think they need these massive deficits to see results, so they’re walking around starving and miserable when they don’t actually need to be. Not fun, and definitely not sustainable.

Oh, and that whole “3,500 calories equals one pound of fat loss” thing? Yeah, that’s from 1958, and it’s honestly pretty inaccurate. Modern science shows weight loss is way more complex and usually slower than that old-school rule suggests. Sorry to burst that bubble.

Metabolic Adaptation and the Weight Loss Plateau

Here’s where your body starts playing tricks on you. When you’re dieting, your metabolism doesn’t just sit there and take it – it fights back. Your resting energy expenditure (that’s the calories you burn just existing) can drop by about 6% beyond what you’d expect from just losing weight. Sometimes it’s even 10-15% more than predicted.

This is called adaptive thermogenesis, and it’s basically your body going into “conservation mode” because it thinks you’re in a famine. Thanks, evolution.

Here’s the problem: those cookie-cutter calorie calculators you find online don’t account for this at all. They just spit out a number and call it a day. And if you go too aggressive with your deficit? You can trigger 3.2 times more metabolic adaptation than if you’d used a smarter, personalized approach.

The Performance Implications for Digital Creators

Let me paint you a picture with a real example. Meet Marcus (not his real name, but totally a real situation). He’s a 31-year-old Roblox developer who downloaded one of those popular fitness apps. The app told him to eat at a certain calorie level, but it overestimated his actual needs by 22%. Yikes.

What happened? Dude started experiencing serious energy crashes, couldn’t focus during coding sessions, and his cognitive performance took a nosedive. Turns out that when you cut calories too aggressively (we’re talking deficits over 20%), you can lose up to 12% of your working memory capacity.

For creators and knowledge workers, this translates to real problems:

- 25% longer project timelines

- More bugs and errors

- Creative blocks

- Generally feeling like your brain is running in slow motion

So yeah, how you calculate your calorie deficit actually matters for your work performance, not just the number on the scale.

Step 1: Establishing Your True Total Daily Energy Expenditure (TDEE)

Choosing the Right TDEE Assessment Equation

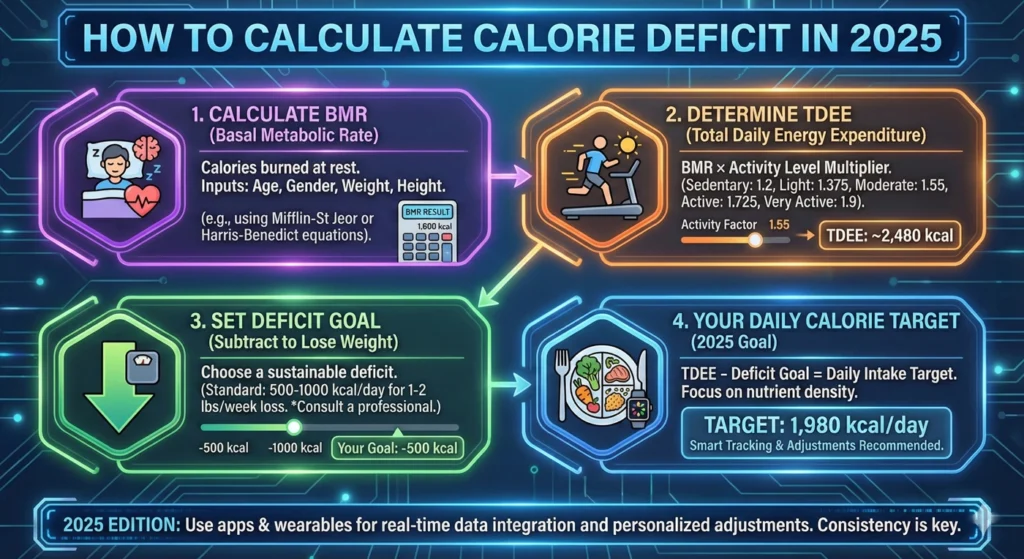

Okay, let’s get into the actual math (don’t worry, I’ll keep it simple). Your TDEE is basically the total calories you burn in a day from everything – just breathing and existing (that’s your BMR), digesting food, fidgeting and moving around (called NEAT), and any actual exercise you do.

To figure this out accurately, you need a good equation. Here are your best options:

Mifflin-St Jeor equation – This one’s solid for most people, with only about a 5% error rate. Pretty reliable.

Cunningham equation – If you’re athletic or have a decent amount of muscle, this one’s even better (4% error rate). Like finding the correct bra size, getting the right formula for your body type matters.

Avoid the Harris-Benedict equation – it’s older and less accurate (8% error rate). We can do better.

Accounting for Activity: NEAT and the Multiplier Ambiguity

Here’s where people really screw things up. You know those activity multipliers in calorie calculators? “Sedentary, Lightly Active, Moderately Active…”? Yeah, people are terrible at categorizing themselves.

I see so many desk workers (looking at you, devs and gamers) who sit for 10+ hours a day but select “moderately active” because they hit the gym three times a week. Nope. That’s not how it works, and it’ll inflate your TDEE estimate by hundreds of calories.

The fix? Track your actual steps for a full week. If you’re averaging under 5,000 steps a day, you’re sedentary – own it. Desk workers often need to apply a correction factor (multiply by 0.8-0.9) to standard calculations because our non-exercise movement is way less than we think.

Validation Protocol: Finding Your True Maintenance Baseline

Alright, here’s the part that requires patience but is totally worth it. You need to validate your TDEE with real data from your actual body. Here’s your 14-day protocol:

- Weigh yourself daily – same time every morning, after you pee, before you eat or drink anything

- Calculate 7-day moving averages – this smooths out random water weight fluctuations (because yes, your weight naturally bounces around by several pounds)

- Log every single thing you eat with a food scale for 14 consecutive days (yeah, you gotta actually weigh stuff – eyeballing doesn’t count)

After 10-14 days, if your weight is stable (within about 1 pound), congrats! The average calories you ate during that period is your true maintenance TDEE. This number is gold because it’s based on your actual body, not some generic formula.

Step 2: Calculating Your Optimal, Personalized Deficit

Body Composition Determines Deficit Magnitude

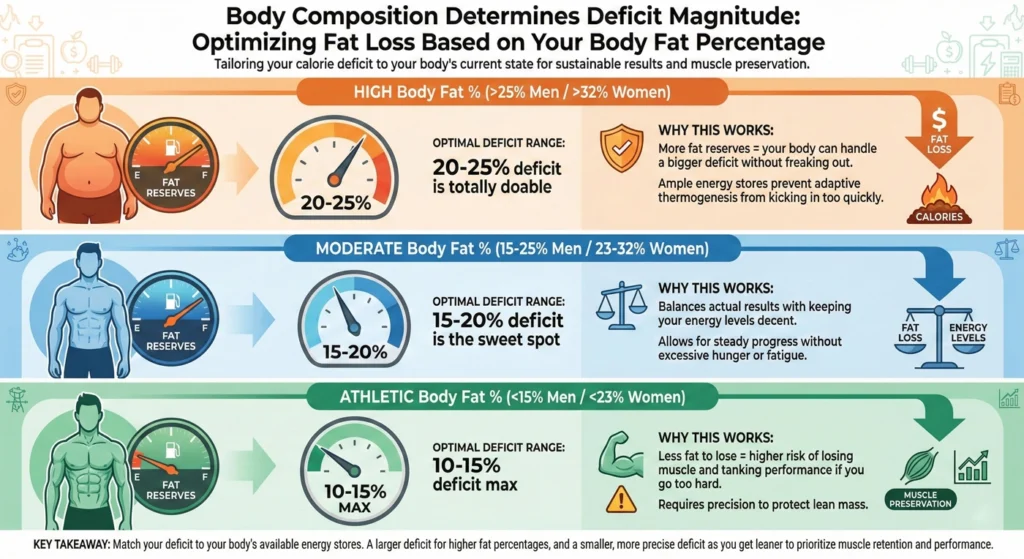

Not everyone should use the same deficit percentage. Your current body fat matters – a lot. Check out this breakdown:

| Body Fat % (Men/Women) | Optimal Deficit Range | Why This Works |

|---|---|---|

| High (>25% / >32%) | 20-25% deficit is totally doable | More fat reserves = your body can handle a bigger deficit without freaking out |

| Moderate (15-25% / 23-32%) | 15-20% deficit is the sweet spot | Balances actual results with keeping your energy levels decent |

| Athletic (<15% / <23%) | 10-15% deficit max | Less fat to lose = higher risk of losing muscle and tanking performance if you go too hard |

Think of it like this: if you’ve got a bigger gas tank (higher body fat), you can afford to use more fuel. If you’re running lean, you gotta be more conservative.

The Cognitive Performance Preservation Ceiling

For anyone whose job involves thinking (so… most of us?), there’s a magic number: 20% deficit maximum. Go beyond that, and you’re basically handicapping your brain.

This is especially true for competitive gamers. If you’ve got a tournament or important stream coming up, maybe dial back to a smaller deficit for those high-performance days. Your reflexes and decision-making will thank you. Just like how an accurate bra size calculator helps you find the right fit, finding your correct deficit percentage is about matching the approach to your specific needs.

Advanced Strategies: Dynamic Adjustments and Metabolic Safeguards

Dynamic Deficit Adjustments and Periodization

Here’s where we separate the amateurs from the pros. Your calorie deficit shouldn’t be set-it-and-forget-it. It needs to be dynamic – meaning it changes based on what’s happening with your body.

Progressive Phase System:

- Weeks 1-2: Start conservative (10-15% deficit) while your body adjusts

- After that: Can increase to moderate (15-20%) if everything’s going well

Metabolic Reset – This is Crucial:

Every 7-10 days (or at minimum every 4-8 weeks), take a “diet break” where you eat at maintenance calories for a few days. I know, I know – it sounds counterintuitive. But this is essential for:

- Metabolic recovery

- Hormone restoration (especially leptin, which regulates hunger)

- Preventing psychological burnout (because constantly dieting sucks)

Carb Periodization:

If you’ve got intensive mental work or creative sessions coming up, strategically bump your carbs to 2-3g per kg of body weight on those days. Your brain loves carbs, and this can really help with focus and performance.

Biofeedback Integration for Real-Time Monitoring

Your body is constantly giving you feedback – you just need to pay attention to it:

- Energy levels – If you’re consistently dragging ass, that’s a sign

- Sleep quality – Excessive deficits can tank your REM sleep by up to 18%

- Heart Rate Variability (HRV) – If you’ve got a fitness tracker that measures this, it’s a great way to monitor stress and recovery

When these metrics start declining, it’s time to ease up on the deficit or take a break.

The Power of Resistance Training and Macro Focus

Let’s talk about keeping your muscle while losing fat (because losing muscle sucks – it tanks your metabolism and makes you look “skinny-fat”).

Resistance training is non-negotiable. Lift weights 3-4 times per week. This signals to your body “Hey, we need this muscle!” so it preferentially burns fat instead.

Protein is your best friend:

- Aim for 1.8-2.2g per kg of body weight

- This preserves lean mass and keeps you fuller longer

- It’s way harder to overeat when you’re prioritizing protein

Don’t forget fats:

- Minimum 0.5g per kg for hormonal health

- Your hormones need fat to function properly (including testosterone, which helps preserve muscle)

Beyond Calories: Supporting Sustainability and Mental Health

Calorie Deficit Sustainability and the 80/20 Rule

Real talk: if your diet makes you miserable, you won’t stick to it. Period. Sustainability beats perfection every single time.

Enter the 80/20 Adherence Framework:

- 80% of your calories come from nutrient-dense whole foods (lean proteins, fruits, veggies, high-fiber starches)

- 20% can be whatever you want – pizza, ice cream, tacos, whatever

This approach crushes cravings and keeps you sane. You’re not “cheating” – you’re following the plan.

What about Intermittent Fasting?

IF can be a helpful tool for managing hunger and staying compliant. Some people love it, some hate it. But here’s the science: it’s not better than regular calorie restriction for long-term weight loss. It might show slightly better short-term fat loss for some people, but the main benefit is if it helps you stick to your deficit more easily. If it works for you, great. If not, skip it.

The Intersection of Metabolism and Mental Health

This is important, so pay attention. Calorie restriction can actually improve mood and reduce depression symptoms, especially if you’re carrying extra weight. That’s cool, right?

But – and this is a big but – excessive restriction can backfire hard:

- Memory problems

- Food obsession

- Compulsive eating

- Emotional eating spirals

- General psychological misery

The key is finding that sweet spot where you’re in a deficit but not suffering.

Interesting science alert: There’s this new class of compounds called Calorie Restriction Mimetics (CRMs) – drugs like Semaglutide (Ozempic/Wegovy) that mimic the metabolic effects of calorie restriction without actually starving yourself. Early research suggests they might help with depression, anxiety, and addiction by influencing reward processing in the brain. Pretty wild stuff, though obviously talk to your doctor about this kind of thing.

Frequently Asked Questions

How do I calculate my calorie deficit accurately?

First, figure out your TDEE using a good equation like Mifflin-St Jeor. Then – and this is critical – validate that number over 14 days of consistent tracking like I outlined above. Once you’ve got your real maintenance calories, subtract 10-20% for a sustainable deficit. That’s your target.

Is calorie counting bad?

Honestly? It’s a tool. Calorie counting itself is backed by science and works for weight management. But it can get messy if you obsess over every single calorie, or if you ignore food quality and just hit your numbers with junk. Some people also develop unhealthy relationships with tracking. Use it as a guide, not a religion.

What should I do if my weight loss plateaus?

Plateaus are completely normal – they happen to everyone. Usually it’s because:

- Your TDEE has dropped as you’ve lost weight (smaller bodies burn fewer calories)

- Water retention is masking fat loss

- Metabolic adaptation has kicked in

Try these fixes

- Recalculate your TDEE based on your new weight

- Increase protein and fiber

- Reduce your deficit slightly (counterintuitive but often works)

- Take a 3-5 day diet break at maintenance calories

How much weight loss is realistic per week?

The sweet spot is 0.5-1% of your body weight per week. So if you weigh 200 pounds, that’s 1-2 pounds per week. If you weigh 150 pounds, that’s 0.75-1.5 pounds per week. Anything faster is usually water weight or you’re losing muscle along with fat.

Conclusion: Systems, Not Willpower

Look, sustainable fat loss isn’t about grinding it out with pure willpower and suffering through a generic 1200-calorie diet you found on some Instagram fitness account. It’s about building a precise, dynamic, personalized system that works with your body, not against it.

By moving beyond those static calculators and implementing:

- Progressive phases

- Metabolic safeguards (like strategic refeeds)

- Data-driven adjustments based on your actual results

…you’ll get consistent fat loss while protecting (or even improving) your mental performance. This is especially important if your livelihood depends on your brain working well.

Key Principles to Remember:

Your optimal deficit is highly individual and changes over time – what worked at the beginning won’t work forever.

Performance preservation requires metabolic safeguards – diet breaks aren’t laziness, they’re strategy.

Strategic periodization beats static approaches every time – your body adapts, so your plan should too.

Sustainable results come from systems, not willpower – build good systems and you won’t need to rely on motivation alone.

So there you have it – how to calculate calorie deficit in 2025 without losing your mind, your muscle, or your ability to focus at work. Start with accurate numbers, adjust dynamically, take strategic breaks, and prioritize your performance along with your weight loss goals.

You’ve got this. Now go forth and deficit responsibly! 💪