Look, I get it. Walking into a hardwood lumber yard for the first time can feel like you’ve stumbled into a secret society where everyone speaks a different language. They’re throwing around terms like “eight quarter” and “FAS” while you’re just trying to figure out how to calculate board feet without embarrassing yourself or getting ripped off.

Here’s the thing – understanding board feet isn’t rocket science, but it’s definitely something you need to nail down before you start dropping serious cash on hardwood. Trust me, I learned this the hard way after buying way too little wood for a project (twice) and then way too much (also twice). So grab your coffee, and let’s break this down together.

- Understanding the Core Unit: What is a Board Foot (BF)?

- The Essential Board Foot Calculation Formulas

- Mastering Hardwood Terminology and Purchasing

- Hardwood Grades and Quality Ratings

- Understanding Surfacing Codes

- Project Planning and Accuracy: Accounting for Loss and Grain

- Lumber Measurements Compared: Volume vs. Area vs. Length

- Advanced Concepts: Log Scaling and Buying Strategies

- Frequently Asked Questions

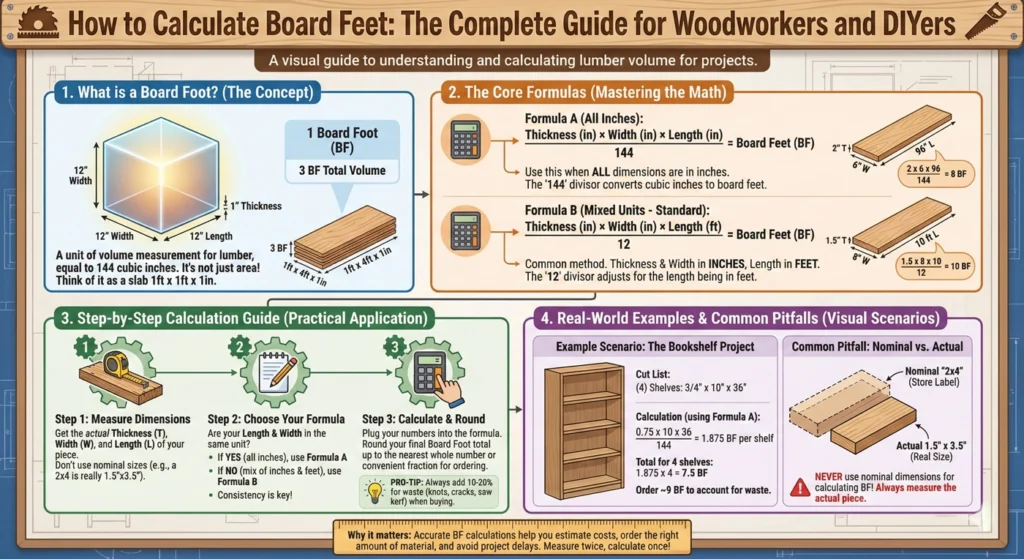

Understanding the Core Unit: What is a Board Foot (BF)?

Defining the Board Foot (BF)

Alright, first things first. A board foot isn’t some ancient measurement invented to confuse you – though I’ll admit it feels that way sometimes.

The Board Foot Defined as Volume: Here’s what you need to burn into your brain – a board foot is all about volume, not just how long something is or how wide. One board foot (you’ll see it abbreviated as BF or BDFT) equals exactly 12 inches long × 12 inches wide × 1 inch thick. That gives you 144 cubic inches of actual wood.

Think of it like this: imagine a perfectly square piece of wood that’s one foot on each side and exactly one inch thick. That’s your baseline board foot. Everything else we calculate is just figuring out how many of those theoretical squares we could carve out of whatever board you’re looking at.

Why Lumber is Sold by Volume

So why don’t lumber yards just sell wood by the piece or by weight like normal stores? Well, picture this scenario: You’ve got two boards sitting next to each other. Both are 8 feet long. But one’s 6 inches wide and the other’s 10 inches wide. One’s an inch thick, the other’s two inches thick. How do you price those fairly? By the board? That makes no sense.

Calculating board feet keeps everything honest because you’re paying for the actual amount of wood you’re getting – what the old-timers call “the meat.” It’s the fairest way to handle lumber pricing when boards come in about a million different sizes. Plus, it stops someone from charging you the same price for a skinny little board as they would for a chunky beast.

Visualizing BF with Examples

Let me give you some real-world examples because this is where it clicks for most people.

Say you’ve got a 4/4 board (don’t worry, I’ll explain that weird fraction in a sec – just know it means 1 inch thick) that’s 6 inches wide and 8 feet long. That bad boy is 4 board feet. Or picture a chunk that’s 2 inches thick × 6 inches wide × 1 foot long – that’s exactly 1 board foot. See? Not so scary once you visualize it.

The Essential Board Foot Calculation Formulas

The Primary Board Foot Formulas Every Woodworker Needs

Okay, here’s where we get into the actual math. Don’t panic – if you can use a calculator, you’re golden.

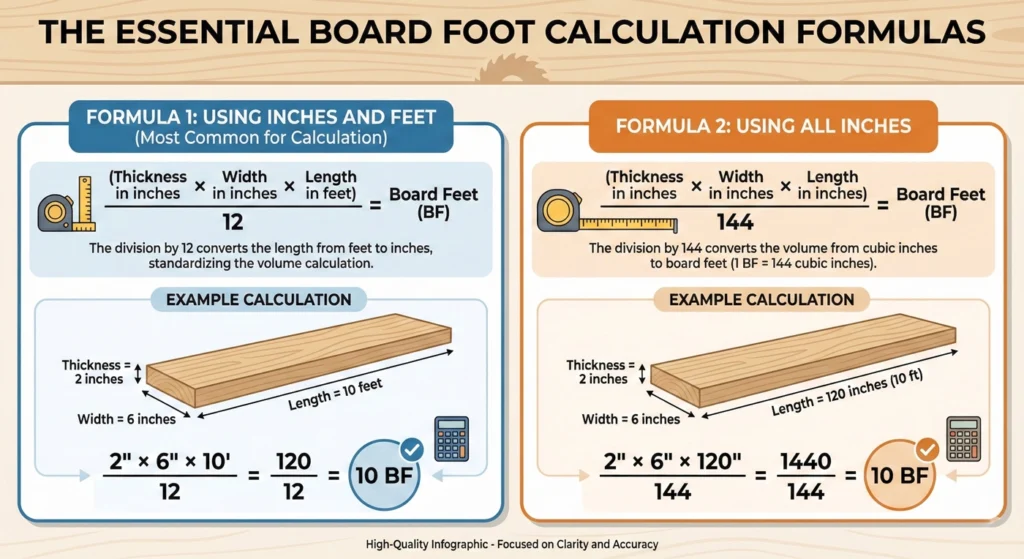

Formula 1: Using Inches and Feet (Most Common for Calculation)

This is the formula I use probably 90% of the time:

Board Feet = (Thickness in inches × Width in inches × Length in feet) ÷ 12

So let’s say you’re eyeing a board that’s 6 inches wide, 1.5 inches thick (that’s 6/4 stock), and 10 feet long. Plug it in: (1.5 × 6 × 10) ÷ 12 = 7.5 board feet. Boom. Done.

This formula is clutch because most lumber is sold by the foot length-wise, but measured in inches for width and thickness. It just makes life easier.

Formula 2: Using All Inches

Sometimes you’re dealing with shorter pieces or weird dimensions, and everything’s in inches. No problem:

Board Feet = (Thickness in inches × Width in inches × Length in inches) ÷ 144

Example time: You’ve got a 2-inch thick board that’s 6 inches wide and 120 inches long (that’s 10 feet, by the way). So: (2 × 6 × 120) ÷ 144 = 10 board feet. Same answer as the first formula, just a different route to get there.

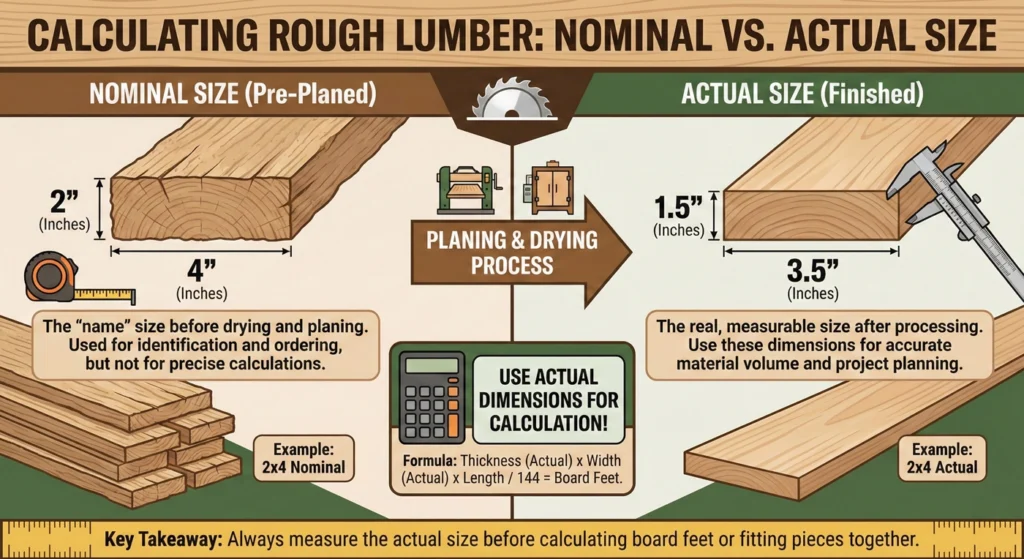

Calculating Rough Lumber: Nominal vs. Actual Size

Here’s where lumber yards will absolutely get you if you’re not paying attention.

Why Use Nominal Dimensions: When you’re calculating board feet for rough or dimensional lumber, you always – and I mean ALWAYS – use the nominal dimensions. That’s the size before it’s been dried and planed down.

Here’s the kicker: if you buy a board that’s already been milled down to ¾” thick, the yard is still going to charge you as if it’s 4/4 stock (1 inch thick nominal). They’re charging you for what it was, not what it is now. I know, it feels a bit like paying for the bones when you order fish, but that’s how the industry works.

Measuring Practices in the Yard: When you’re measuring rough lumber at the yard, here’s a pro move – measure the width at the narrowest usable point. Some dealers are super precise, others will see a board that’s 7.5 inches wide and round up to 8 inches when they’re calculating your total. Know what you’re being charged for, and don’t be afraid to double-check their math. Bring a tape measure. Seriously.

Mastering Hardwood Terminology and Purchasing

Decoding Lumber Thickness: The Quarter System

Alright, remember those weird fractions I mentioned? Time to decode them.

Quarter Notation Explained: Hardwood dealers use this quarter system where the top number tells you how many quarter-inches thick the board is (nominally). It’s like they’re speaking in fractions just to mess with us.

- 4/4: Say “four quarter” (don’t say “four fourths” or “one” – you’ll out yourself as a newbie). This means nominally 1 inch thick. After it’s been surfaced, it’s usually about ¾” thick.

- 8/4: “Eight quarter” – that’s nominally 2 inches thick. Surfaced, you’re looking at about 1¾” thick.

- Other Sizes: You’ll also run into 5/4, 6/4, 10/4, 12/4, and even 16/4 for the really beefy stuff.

Buying for Final Thickness: Here’s a golden rule that’ll save your bacon: always buy lumber that’s ¼” to ½” thicker than your final desired dimension. Wood needs to be flattened, planed, and sometimes you’ll hit a surprise knot or weird grain. That extra thickness is your insurance policy against having to start over.

Hardwood Grades and Quality Ratings

Grades are basically the lumber world’s way of saying “this is how pretty and usable your board is going to be.” And yeah, prettier costs more.

Highest Grades (Clear Cuttings)

FAS (First and Seconds): This is the champagne of hardwood lumber. Big, wide boards that are mostly clear of defects. Beautiful stuff, but you’ll pay through the nose for it. If you’re building a dining table that’ll be the centerpiece of your home, FAS might be worth it.

F1F (FAS 1-Face) and Select: These boards have one gorgeous FAS face and the other side meets lower standards (No. 1 Common). Perfect if only one side will show in your project. Why pay for two perfect faces if you only need one?

Common Working Grades

No. 1 Common: This is your workhorse grade – standard furniture quality. You’ll get good clear sections for cuts, but you’ll need to work around some knots and defects. Honestly, for most projects, this is the sweet spot between quality and cost.

No. 2A Common: Standard cabinet grade. It’s totally usable for clear short and medium cuts, just requires more planning and waste.

Pro tip: Most people default to buying FAS because it’s “the best,” but I’ve saved literally hundreds of dollars by carefully picking through No. 1 Common stock. Take your time, inspect the boards, and you’ll find gems.

Understanding Surfacing Codes

These little codes tell you how much work has already been done to the wood, which directly impacts price and how much milling you’ll need to do yourself.

Rough Lumber: Fresh from the sawmill, completely unprocessed. All four sides are rough, nothing’s parallel or square. You’ll need to do all the milling yourself, but it’s usually the cheapest way to buy.

S2S (Surfaced Two Sides): Two faces have been planed flat and parallel to each other. You still need to joint the edges yourself to get them straight and square.

S4S (Surfaced Four Sides): This is fully milled – two parallel faces and two edges that are straight and square to those faces. Sounds perfect, right? Except wood moves with humidity changes, so that “perfectly straight” board might twist or cup on you if it wasn’t properly dried or acclimated. Still super convenient though.

SL1E (Straight Line One Edge): One edge has been jointed straight and square to the face. Less common, but handy when you need it.

Project Planning and Accuracy: Accounting for Loss and Grain

Here’s where beginners get absolutely destroyed – they calculate their exact needs and buy exactly that much wood. Don’t be that person.

The Necessity of Over-Ordering Lumber

Required Waste Margin: Listen up, because this is critical. You need to buy 15-50% more wood than your minimum calculated board footage. I know that sounds insane, but here’s why:

- Saw blade kerf eats up material

- You’ll need to cut around defects you didn’t see at first

- Grain matching requires options

- Milling loss from getting everything flat and square

- Mistakes happen (especially on complicated cuts)

The Accurate Method (Cut Diagram): There’s the “lazy way” and the “accurate way” to buy lumber. The lazy way is just calculating total board feet and buying that much. The accurate way? Draw out exactly how you’ll cut each piece from specific board sizes.

Let me give you an example: Say your project needs four pieces that are each 6 feet long. If you just buy enough board feet in random short boards, you’re screwed. You need to make sure you actually buy boards that are 6+ feet long. A cut diagram solves this.

Acclimation and Movement: And here’s something nobody tells beginners – wood moves. A lot. Especially presurfaced lumber. When humidity changes, boards can bow, cup, or twist like they’re auditioning for Cirque du Soleil. Let your wood acclimate in your shop for days (ideally weeks) before you mill it. I learned this one the hard way when a “perfectly flat” board turned into a potato chip overnight.

The Importance of Wood Cut Types (Stability)

Not all boards are created equal, even if they’re the same species. How the wood was cut from the log massively impacts how it behaves.

Flatsawn (Plain Sawn): This is the most common cut. You get those beautiful cathedral grain patterns on the face. Looks gorgeous, but here’s the catch – most seasonal expansion happens across the width, making it the least stable option. Great for projects where movement won’t kill you.

Quartersawn: The face grain runs pretty straight, and the end grain is vertical. This cut is incredibly stable because wood movement happens mostly in the thickness direction (which doesn’t matter as much). Perfect for table tops, cabinet doors, or anywhere you need dimensional stability. It’s pricier though, because it’s more work to cut this way.

Rift Sawn: The rarest cut. Dead straight grain on the face, and stability is better than flatsawn. Super pretty, super expensive, and honestly hard to find outside of specialty dealers.

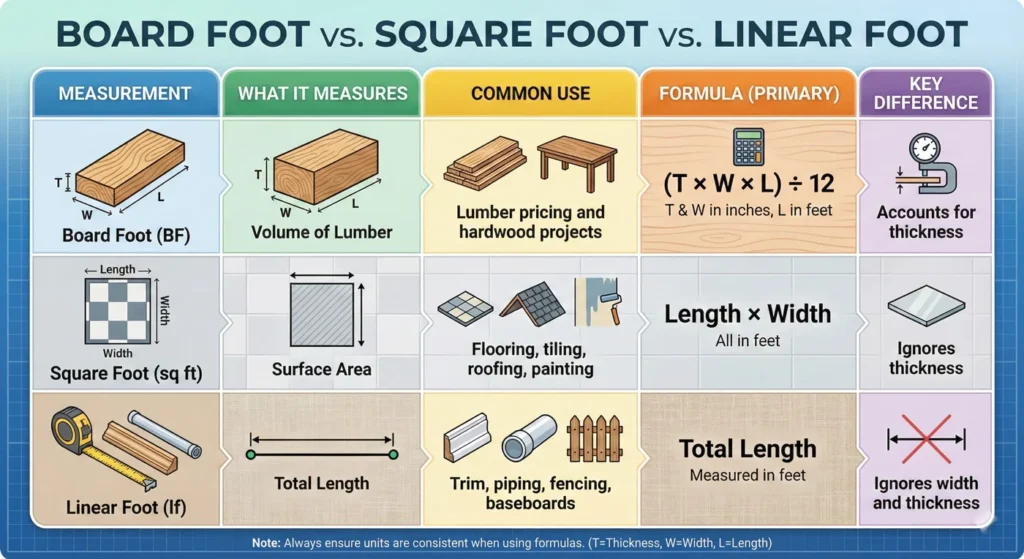

Lumber Measurements Compared: Volume vs. Area vs. Length

This is where people get seriously confused, so let me break down the difference between board feet, square feet, and linear feet.

Board Foot vs. Square Foot vs. Linear Foot

| Measurement | What It Measures | Common Use | Formula (Primary) | Key Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Board Foot (BF) | Volume of Lumber | Lumber pricing and hardwood projects | (T × W × L) ÷ 12 | Accounts for thickness |

| Square Foot (sq ft) | Surface Area | Flooring, tiling, roofing | Length × Width (in feet) | Ignores thickness |

| Linear Foot (lf) | Total Length | Trim, piping, fencing | Total Length in Feet | Ignores width and thickness |

Here’s the important bit: you can’t directly convert board feet to square feet without knowing the thickness. It’s like asking “how many miles per gallon is this apple?” The units measure different things.

Advanced Concepts: Log Scaling and Buying Strategies

Okay, we’re getting into the deep end here, but this stuff makes you look like a pro at the lumber yard.

Estimating Volume in Logs (Log Rules)

Ever wonder how timber companies figure out how much lumber they’ll get from a standing tree? They use these wild formulas called “log rules.”

Log Scaling Methods: The three big ones in the U.S. and Canada are the Doyle, Scribner Decimal C, and International ¼” rule.

The Doyle rule is super common for hardwood logs (especially in Tennessee), but it’s kind of wonky – it underestimates small logs and overestimates big ones. The International ¼” rule is generally the most accurate because it accounts for how logs taper as they go up the tree.

Unless you’re buying whole logs or getting into forestry, you probably don’t need to memorize this stuff. But now you know why your lumber yard guy can estimate board feet by just glancing at a log. It’s not magic – it’s math.

Essential Pro Tips for Buying Lumber

Let me drop some wisdom I wish someone had told me years ago:

Pricing: Hardwood prices bounce around like a toddler on sugar. Most yards don’t even list current prices because they change so often. Always – and I mean always – ask the price per board foot before you start loading up. Better yet, call ahead so you don’t have sticker shock at checkout.

Selecting Boards: Don’t be shy at the lumber yard. Bring chalk to mark boards you want. Dig through the stack. Check for straight grain, minimal defects, and the right dimensions. The good yards expect this and won’t hassle you about it. If they do, find a different yard.

Online Buying: Buying lumber online is a bit like online dating – manage your expectations. You can’t see the actual grain pattern, so order extra. Also check what length and width boards they typically send. Some online dealers are fantastic (Bell Forest Products gets a lot of love), but you’re taking a gamble on the specific boards you’ll receive.

Finding Lumber: Big box stores are convenient, but dedicated hardwood lumber yards are where you’ll find quality and selection. They’ll have knowledgeable staff who can actually help you calculate board feet and plan your project. Local sawmills are also goldmines if you can find them – often cheaper and you’re supporting local business.

Frequently Asked Questions

How do lumber yards measure board feet on irregular slabs?

Good question. Reputable suppliers charge you for the “red meat” – the actual usable wood – and won’t count big cracks, bark edges, or rotted sections. Sketchy dealers? They’ll measure at the widest point and charge you for everything, including the junk. This is why building relationships with good yards matters.

How many board feet are in a standard 8-foot 2×4?

Using the nominal dimensions (2″ × 4″), an 8-foot long 2×4 works out to: (2 × 4 × 8) ÷ 12 = 5.33 board feet. Even though the actual dimensions are smaller (like 1.5″ × 3.5″), you’re charged for the nominal size.

What does S2S mean when buying wood?

S2S stands for “Surfaced Two Sides” – both faces have been planed flat and parallel. You’ll still need to square up the edges yourself, but it’s a time-saver if you don’t have a big planer.

What is the most stable type of cut for wood?

Quartersawn is your best bet for stability. The wood movement is minimal in the directions that matter. Some purists will argue that riven wood (split along natural grain lines) is even more stable, but good luck finding that at your local lumber yard.

Why is it so confusing to calculate board feet?

Honestly? Because the word “foot” makes everyone think about length only (linear feet), when board feet is actually about volume. Plus, the whole nominal vs. actual size thing trips people up. And using those quarter fractions instead of just saying “1 inch thick” doesn’t help. But once it clicks, it clicks. You’ve got this.

Look, how to calculate board feet might seem intimidating at first, but it’s really just multiplication and division. The hardest part isn’t the math – it’s understanding the terminology and not getting taken for a ride at the lumber yard.

Start with simple projects, use those formulas I gave you, and don’t be afraid to ask questions at the yard. Everyone started where you are now. The crusty old guy who seems annoyed? He was once a newbie too, even if he won’t admit it.

Most importantly, remember to over-order. Seriously. That 20% extra material will save you from making a second trip when you realize you’re three inches short on a critical piece. Been there, done that, got the T-shirt.

Now get out there and buy some wood. You’ve got projects to build.